著名医師による解説が無料で読めます

すると翻訳の精度が向上します

目的:5週間の介入後の子どもの果物と野菜の摂取に対する学校の果物と野菜のサブスクリプションの効果を測定する。 設定:デンマークの7つの小学校。 設計と方法:介入学校(n = 4)には、1日あたりの1ピースで構成される果物と野菜のサブスクリプションが提供されました。別の自治体にあるコントロールスクールは、サブスクリプションを提供されませんでした。果物と野菜の摂取量は、ベースラインで測定され、サブスクリプションの開始から5週間後に測定されました。食事評価には、2つの方法が使用されました。総食品摂取量と、果物と野菜のみを含む食物頻度アンケート(FFQ)を含む24時間前のリコールフォームです。 被験者:6〜10歳の子供(介入学校のn = 804、コントロールスクールのn = 689)。食事評価の反応率は31%でした。 結果:介入学校では、子どもの45%がサブスクリプションに登録しています。5週間の介入の後、加入者と非担保者の両方が、学校の日ごとにそれぞれ果物の摂取量を0.4(p = 0.019)および0.3(p = 0.008)断片に増やしましたが、植物摂取量では変化は観察されませんでした。主に果実摂取量の一貫した増加により、総摂取量は0.4ピース/学校の日(p = 0.008)までにのみ増加しました。摂取量の摂取量の変化は、統制学校で測定されませんでした。FFQはそうではありませんでしたが、24時間のリコールアンケートのみがサブスクリプションの変更をピックアップするのに十分敏感でした。 結論:サブスクリプションを伴う5週間は、サブスクライバーと非担保者の両方に影響を与え、果物の摂取量を増やしました。これは、サブスクリプションが非潜水者の両親を刺激して子供に果物を供給するという追加の効果があることを示している可能性があります。結果は、このタイプのプログラムの効果を評価することの重要性と、評価研究の設計に必要な注意を強調しています。

目的:5週間の介入後の子どもの果物と野菜の摂取に対する学校の果物と野菜のサブスクリプションの効果を測定する。 設定:デンマークの7つの小学校。 設計と方法:介入学校(n = 4)には、1日あたりの1ピースで構成される果物と野菜のサブスクリプションが提供されました。別の自治体にあるコントロールスクールは、サブスクリプションを提供されませんでした。果物と野菜の摂取量は、ベースラインで測定され、サブスクリプションの開始から5週間後に測定されました。食事評価には、2つの方法が使用されました。総食品摂取量と、果物と野菜のみを含む食物頻度アンケート(FFQ)を含む24時間前のリコールフォームです。 被験者:6〜10歳の子供(介入学校のn = 804、コントロールスクールのn = 689)。食事評価の反応率は31%でした。 結果:介入学校では、子どもの45%がサブスクリプションに登録しています。5週間の介入の後、加入者と非担保者の両方が、学校の日ごとにそれぞれ果物の摂取量を0.4(p = 0.019)および0.3(p = 0.008)断片に増やしましたが、植物摂取量では変化は観察されませんでした。主に果実摂取量の一貫した増加により、総摂取量は0.4ピース/学校の日(p = 0.008)までにのみ増加しました。摂取量の摂取量の変化は、統制学校で測定されませんでした。FFQはそうではありませんでしたが、24時間のリコールアンケートのみがサブスクリプションの変更をピックアップするのに十分敏感でした。 結論:サブスクリプションを伴う5週間は、サブスクライバーと非担保者の両方に影響を与え、果物の摂取量を増やしました。これは、サブスクリプションが非潜水者の両親を刺激して子供に果物を供給するという追加の効果があることを示している可能性があります。結果は、このタイプのプログラムの効果を評価することの重要性と、評価研究の設計に必要な注意を強調しています。

OBJECTIVE: To measure the effect of a school fruit and vegetable subscription on children's intake of fruit and vegetables after 5 weeks of intervention. SETTING: Seven primary schools in Denmark. DESIGN AND METHODS: Intervention schools (n=4) were offered a fruit and vegetable subscription comprising one piece per day. Control schools situated in another municipality were not offered the subscription. Intake of fruit and vegetables was measured at baseline and 5 weeks after the start of the subscription. Two methods were used for dietary assessment: a pre-coded 24-hour recall form including total food intake and a food-frequency questionnaire (FFQ) including only fruit and vegetables. SUBJECTS: Children aged 6-10 years (n=804 from intervention schools and n=689 from control schools). Response rate in the dietary assessment was 31%. RESULTS: At intervention schools 45% of the children enrolled in the subscription. After 5 weeks of intervention, both subscribers and non-subscribers had increased their intake of fruit by 0.4 (P=0.019) and 0.3 (P=0.008) pieces per school day, respectively, but no change was observed in vegetable intake. Total intake increased only for non-subscribers by 0.4 piece/school day (P=0.008) mainly due to the consistent increase in fruit intake. No change in intake was measured at control schools. Only the 24-hour recall questionnaire was sensitive enough to pick up the changes of the subscription, whereas the FFQ was not. CONCLUSION: Five weeks with the subscription affected both subscribers and non-subscribers to increase intake of fruit. This may indicate that the subscription had an additional effect of stimulating parents of non-subscribers to supply their children with fruit. The results stress the importance of evaluating the effect of this type of programme, and the carefulness needed in designing the evaluation study.

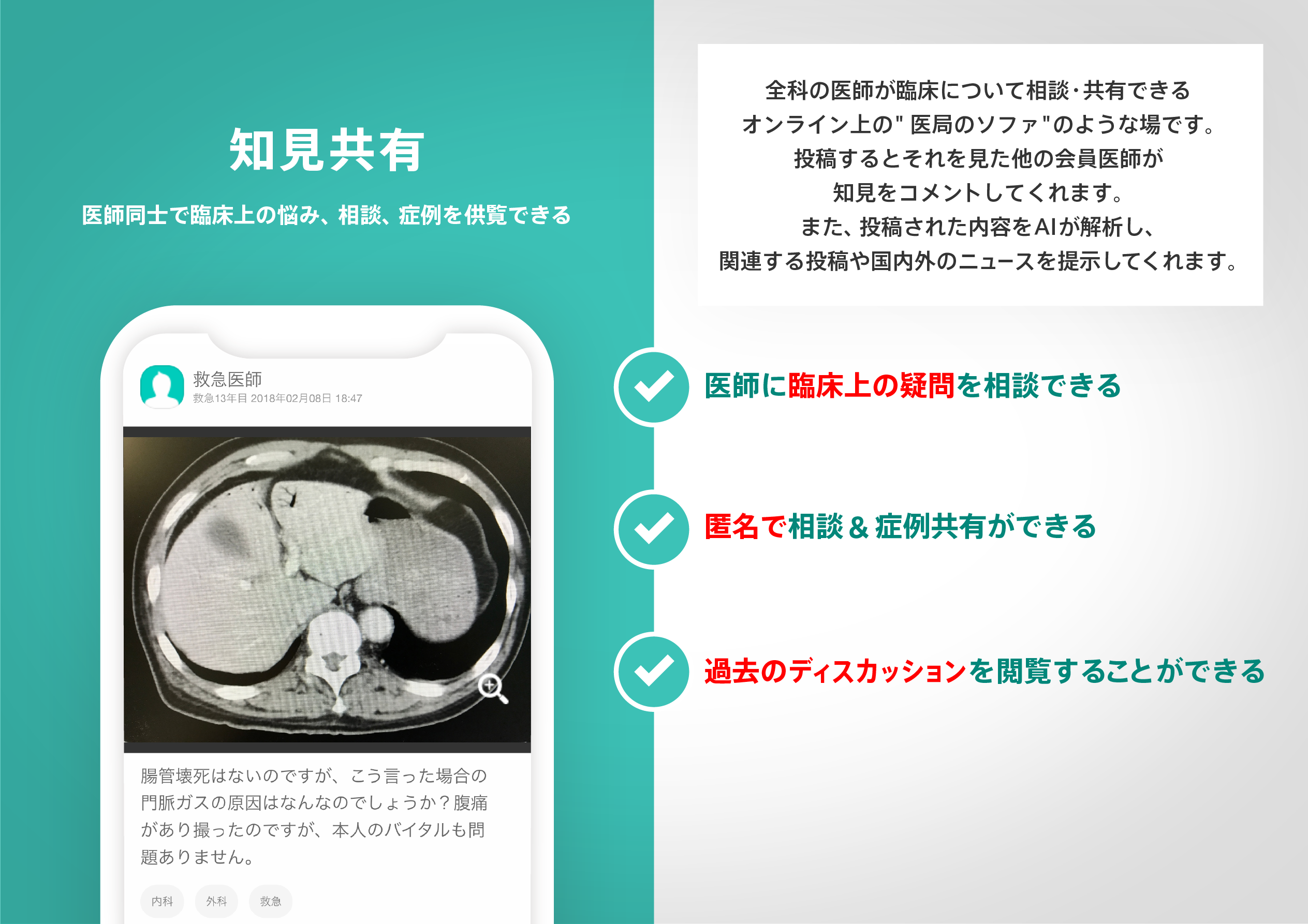

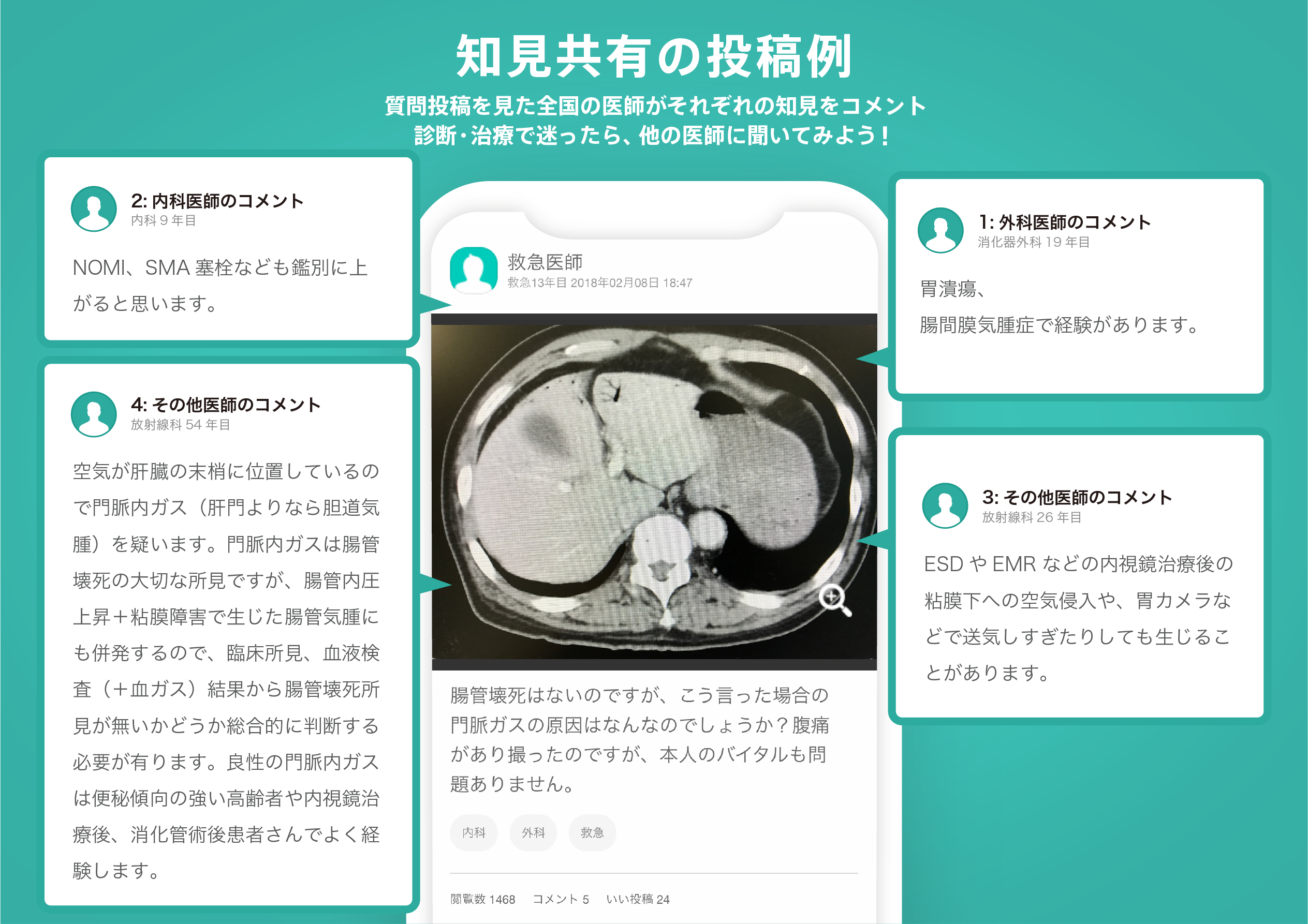

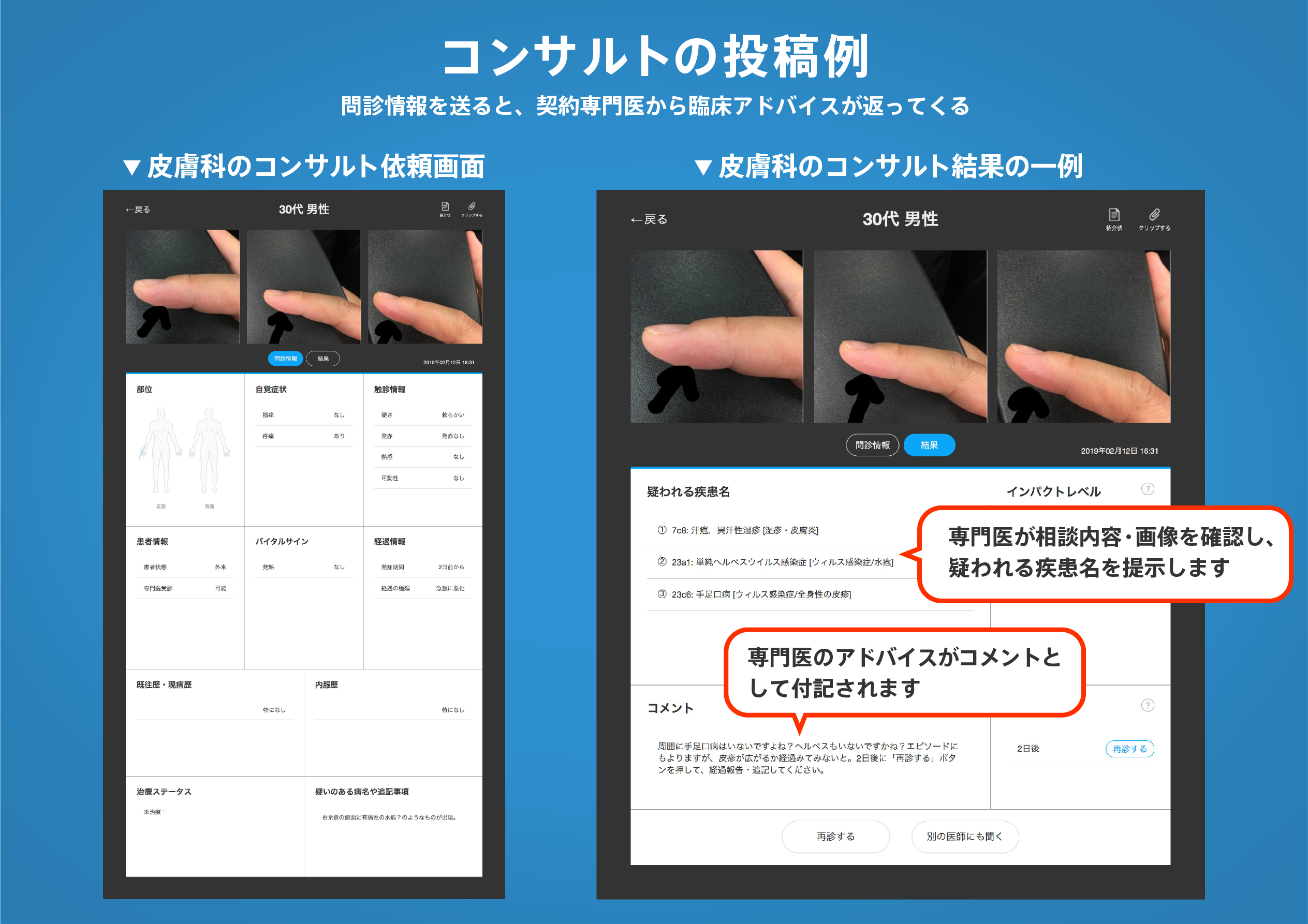

医師のための臨床サポートサービス

ヒポクラ x マイナビのご紹介

無料会員登録していただくと、さらに便利で効率的な検索が可能になります。