著名医師による解説が無料で読めます

すると翻訳の精度が向上します

背景:南アジアの性の不均衡の問題はよく認識されていますが、その社会的パターンについてはあまり知られていません。性別の割合における社会的パターニングは、1996年に出生前診断技術(PNDT)法の実施の前後にインドの乳児の間で調査されました。この法律は、胎児の性決定とその後の選択的断絶の技術の誤用を規制しています。 方法:多変量回帰分析は、乳児を持つ世帯の全国的に代表的なサンプルからの時系列データで実行されました。結果は、男性の幼児を持つことのログオッズでした。世帯収入、親の教育、社会的カースト、PNDT法の実施前後の期間を表す変数、および居住状態が関心の主な予測因子でした。 結果:男性の乳児が収入四分位数で増加する確率。中等後の教育を受けた家庭長は、正式な教育を受けていない人よりも、男性乳児を持つというオッズ比が高かった。雄の乳児を持つ確率は、高いカーストグループと低いカーストグループの間で違いはなく、配偶者の教育的達成とは関連していませんでした。パンジャブは、ケララと比較して雄の乳児を持つというオッズ比が高かった。一方、ケララは、残りのインドの州と特に違いはありませんでした。男性乳児を持つ確率は、PNDT以前とPNDT後の期間で類似していた。PNDT後の期間では、男性の乳児がいる可能性のある収入勾配は実質的に弱体化しました。 結論:インドの乳児間の性別の分布の社会的分析は、社会経済的状況の改善も、社会的規範と一致していない政策の導入も、インドの性の不均衡を正常化する可能性が高いことを示唆しています。

背景:南アジアの性の不均衡の問題はよく認識されていますが、その社会的パターンについてはあまり知られていません。性別の割合における社会的パターニングは、1996年に出生前診断技術(PNDT)法の実施の前後にインドの乳児の間で調査されました。この法律は、胎児の性決定とその後の選択的断絶の技術の誤用を規制しています。 方法:多変量回帰分析は、乳児を持つ世帯の全国的に代表的なサンプルからの時系列データで実行されました。結果は、男性の幼児を持つことのログオッズでした。世帯収入、親の教育、社会的カースト、PNDT法の実施前後の期間を表す変数、および居住状態が関心の主な予測因子でした。 結果:男性の乳児が収入四分位数で増加する確率。中等後の教育を受けた家庭長は、正式な教育を受けていない人よりも、男性乳児を持つというオッズ比が高かった。雄の乳児を持つ確率は、高いカーストグループと低いカーストグループの間で違いはなく、配偶者の教育的達成とは関連していませんでした。パンジャブは、ケララと比較して雄の乳児を持つというオッズ比が高かった。一方、ケララは、残りのインドの州と特に違いはありませんでした。男性乳児を持つ確率は、PNDT以前とPNDT後の期間で類似していた。PNDT後の期間では、男性の乳児がいる可能性のある収入勾配は実質的に弱体化しました。 結論:インドの乳児間の性別の分布の社会的分析は、社会経済的状況の改善も、社会的規範と一致していない政策の導入も、インドの性の不均衡を正常化する可能性が高いことを示唆しています。

BACKGROUND: While the issue of sex imbalance in South Asia is well recognised, less is known about its social patterning. Social patterning in the proportion of sexes was investigated among infants in India before and after the implementation of the Pre-Natal Diagnostic Techniques (PNDT) Act in 1996. The act regulates the misuse of technologies for sex determination of fetuses and subsequent selective abortion. METHODS: Multivariable regression analysis was performed on time series data from a nationally representative sample of households with infants. The outcome was log odds of having a male infant. Household income, parental education, social caste, a variable representing periods before and after the implementation of the PNDT Act and state of residence were the main predictors of interest. RESULTS: The odds of having a male infant increased with income quartiles. Heads of household with post-secondary education had a higher odds ratio of having a male infant than those with no formal education. The odds of having a male infant did not differ between high and low caste groups, and was not associated with the educational attainment of the spouse. Punjab had a higher odds ratio of having a male infant compared with Kerala. Kerala, meanwhile, was not particularly different from the remaining Indian states. The odds of having a male infant were similar in the pre- and post-PNDT periods. In the post-PNDT period, the income gradient in the odds of having a male infant was substantially weakened. CONCLUSION: Social analysis of the distribution of sexes among infants in India suggests that neither improvements in socioeconomic circumstances nor introducing policies that are not aligned with societal norms and preferences are likely to normalise the sex imbalance in India.

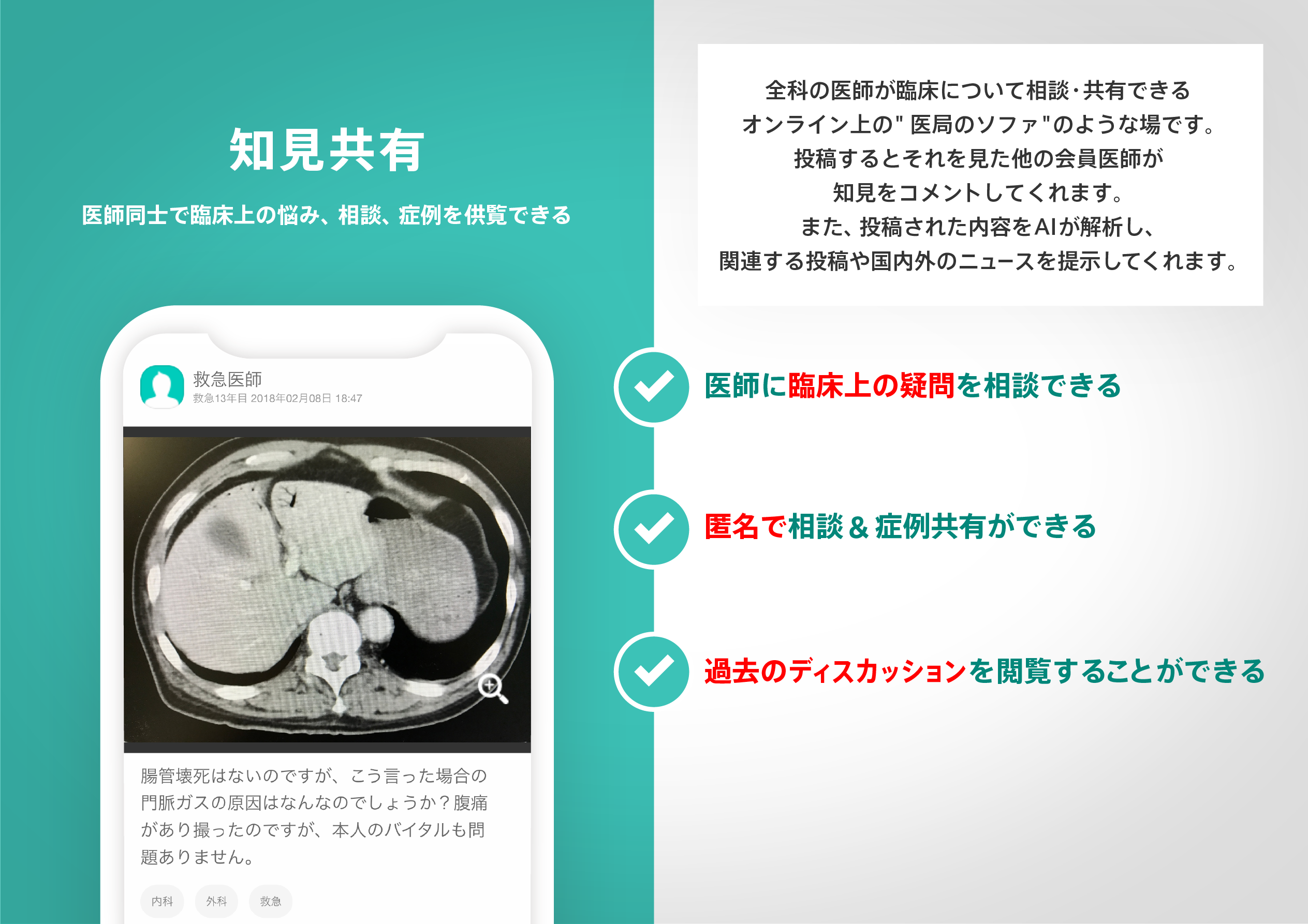

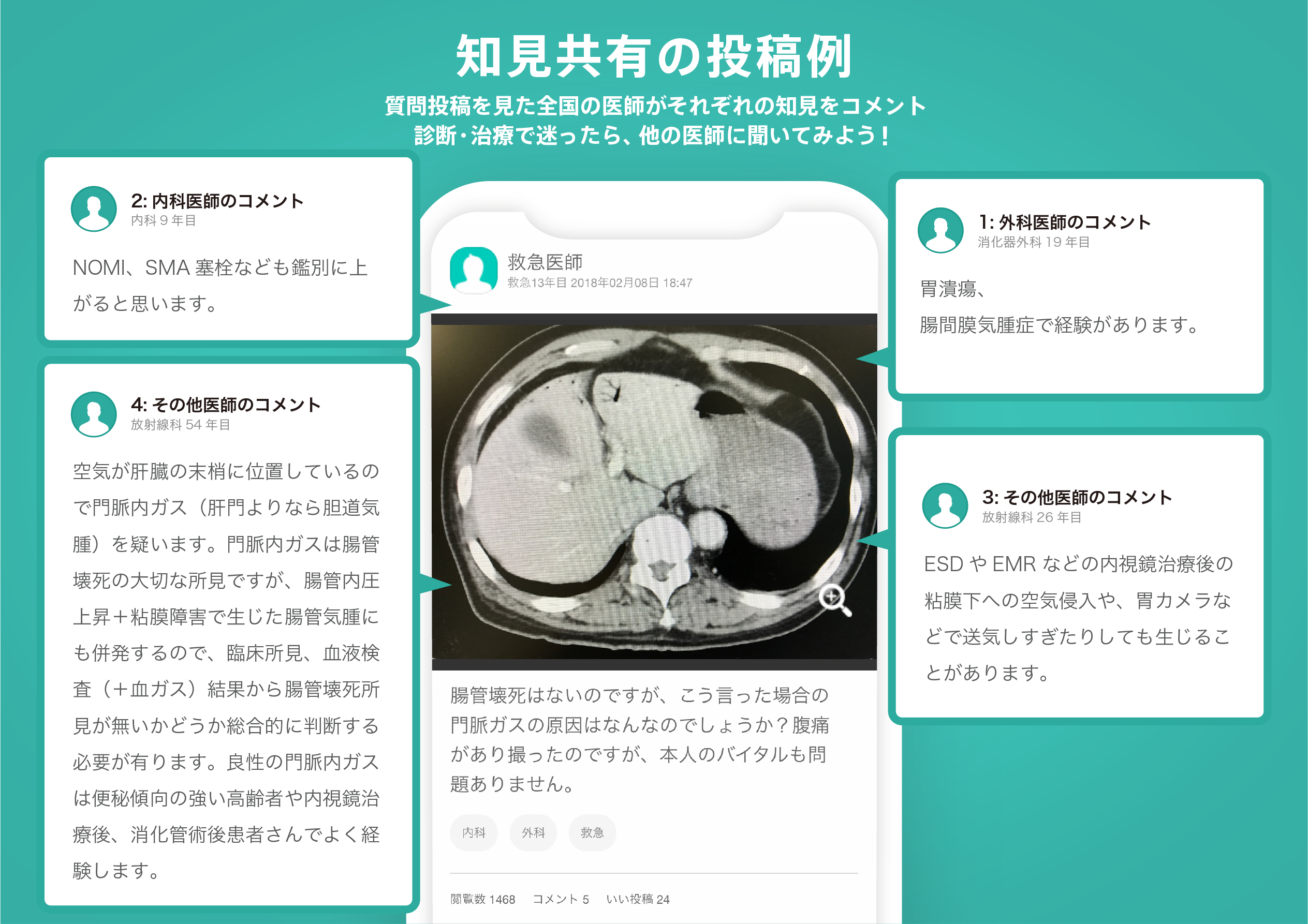

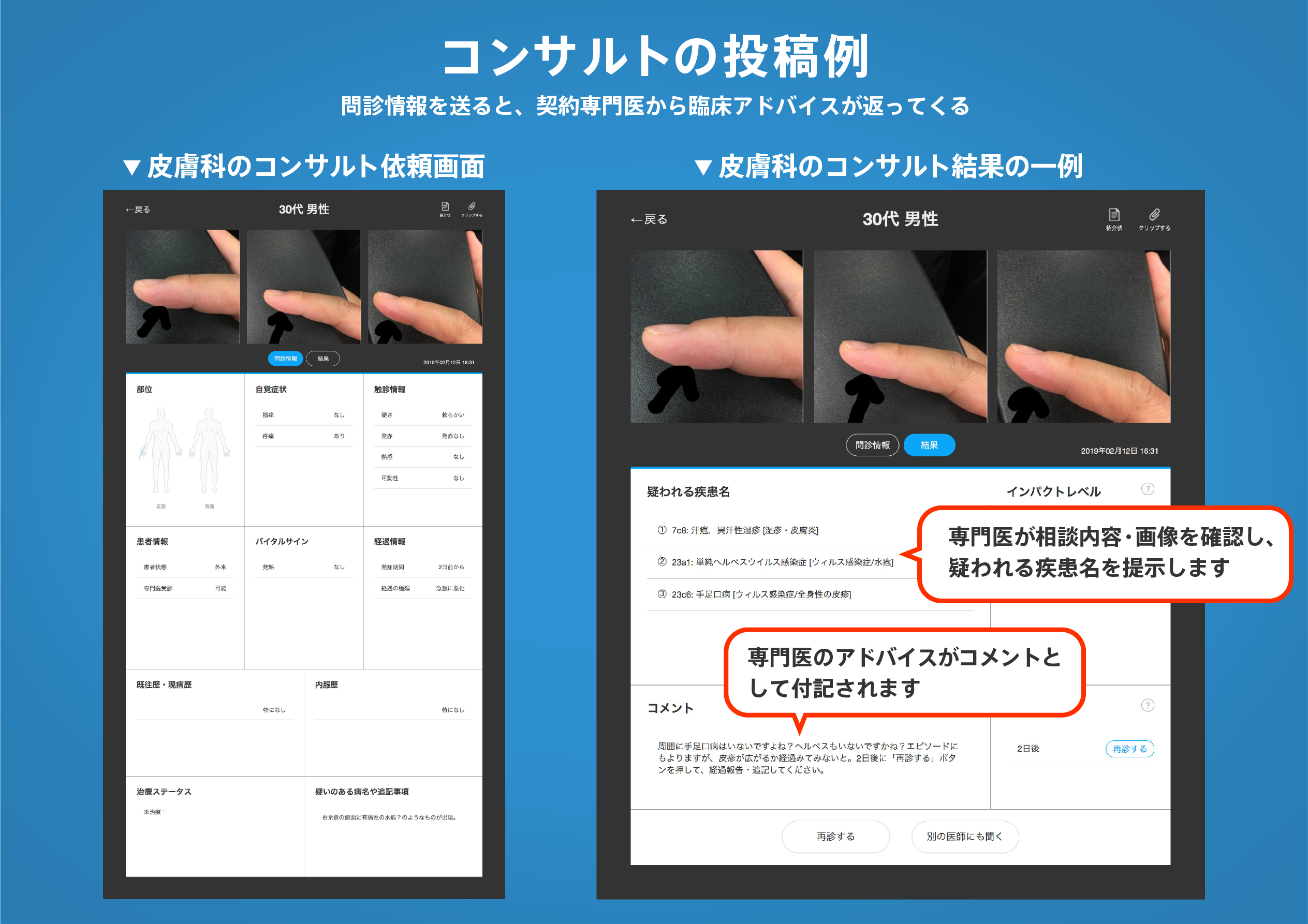

医師のための臨床サポートサービス

ヒポクラ x マイナビのご紹介

無料会員登録していただくと、さらに便利で効率的な検索が可能になります。