著名医師による解説が無料で読めます

すると翻訳の精度が向上します

背景:双子の妊娠の出生前の追跡中に、リスクの高いグループを特定し、周産期ケアを計画するためには、出生時体重の正確な識別と出生時体重の不一致が重要です。残念ながら、2次元超音波による出生時体重の不一致の出生前評価は、最適ではありません。 目的:この研究の目的は、2次元の超音波(超音波推定胎児重量)と磁気共鳴画像診断(磁気共鳴を推定する胎児重量)に基づいて、双子の妊娠を運ぶ女性の実際の出生級と前向きに比較することでした。 研究デザイン:この倫理委員会が承認した研究について、書面によるインフォームドコンセントが得られました。2011年9月から2015年12月の間、および分娩前の48時間以内に、34.39.0週間の双子の妊娠に由来する66の胎児で、超音波推定胎児体重と磁気共鳴を推定する胎児体重が実施されました。妊娠。胎児の体積の手動測定に由来する磁気共鳴を推定する胎児重量。磁気共鳴を推定した胎児体重と超音波推定胎児体重測定と出生級の比較は、ブランドとアルトマンによって記述されたパラメーターを計算することによって実行されました。磁気共鳴を推定する胎児体重と超音波推定胎児体重を使用して、小規模年齢の新生児の予測のために、受信機操作特性曲線が構築されました。双子1と2の場合、相対誤差またはパーセンテージ誤差は次のように計算されました:(出生体重 - 超音波推定胎児重量(または磁気共鳴測定胎児重量)/出生時体重)×100(パーセンテージ)。さらに、超音波推定胎児重量、磁気共鳴測定胎児重量、および出生級の不一致は、100倍(推定胎児の推定推定胎児重量)/より大きな推定胎児体重として計算されました。超音波を推定する胎児体重の不一致と出生級の不一致は、線形回帰分析とピアソンの相関係数を使用して相関しました。同じことが、磁気共鳴を推定する胎児の体重と出生老年度の不一致との間で行われました。データを比較するために、χ2、McNemarテスト、スチューデントTテスト、およびWilcoxon署名ランクテストを必要に応じて使用しました。Fisher R-to-Z変換を使用して、相関係数を比較しました。 結果:超音波推定胎児体重のバイアスと95%の一致の制限は、2.99(-19.17%から25.15%)および磁気共鳴を推定する胎児体重0.63(-9.41%から10.67%)です。超音波推定胎児体重と比較して、磁気共鳴を推定する胎児重量と実際の出生級の間で一致の制限が良好でした。66人の新生児のうち、27人(40.9%)は10才か以下の重量であり、5才以下の21人(31.8%)でした。出生時重量の予測のための受信機操作特性曲線の下の領域は、出生前超音波による10剤以下を0.895(p <.001; SE、0.049)、磁気共鳴画像による0.946(p <.001; SE、0.024)でした。受信機を操作する特性曲線のペアワイズ比較は、受信機操作特性曲線の下の領域間に有意差を示しました(差、0.087、p = .049; SE、0.044)。超音波推定胎児体重の相対誤差は6.8%であり、磁気共鳴を推定する胎児重量、3.2%(p <.001)。超音波推定胎児重量を使用すると、胎児の37.9%(66の25)が実際の出生時体重の±10%の範囲外で推定されましたが、磁気共振胎児体重(p <.001)で6.1%(66の4)に低下しました。超音波推定胎児体重の不一致と出生級の不一致は、線形方程式に従って有意に相関していました:超音波推定胎児体重の不一致= 0.03+ 0.91×出生体重(r = 0.75; p <.001);ただし、相関は磁気共鳴画像法でより良くなりました:磁気共鳴を推定する胎児体重の不一致= 0.02+ 0.81×出生時体重(r = 0.87; p <.001)。 結論:双子の妊娠では、分娩の直前に実行される磁気共振胎児体重がより正確であり、超音波及ぼす胎児体重よりも少量の新生児が大幅に優れていると予測します。超音波と比較して、磁気共鳴画像法では、出生老年度の不一致の予測が優れています。

背景:双子の妊娠の出生前の追跡中に、リスクの高いグループを特定し、周産期ケアを計画するためには、出生時体重の正確な識別と出生時体重の不一致が重要です。残念ながら、2次元超音波による出生時体重の不一致の出生前評価は、最適ではありません。 目的:この研究の目的は、2次元の超音波(超音波推定胎児重量)と磁気共鳴画像診断(磁気共鳴を推定する胎児重量)に基づいて、双子の妊娠を運ぶ女性の実際の出生級と前向きに比較することでした。 研究デザイン:この倫理委員会が承認した研究について、書面によるインフォームドコンセントが得られました。2011年9月から2015年12月の間、および分娩前の48時間以内に、34.39.0週間の双子の妊娠に由来する66の胎児で、超音波推定胎児体重と磁気共鳴を推定する胎児体重が実施されました。妊娠。胎児の体積の手動測定に由来する磁気共鳴を推定する胎児重量。磁気共鳴を推定した胎児体重と超音波推定胎児体重測定と出生級の比較は、ブランドとアルトマンによって記述されたパラメーターを計算することによって実行されました。磁気共鳴を推定する胎児体重と超音波推定胎児体重を使用して、小規模年齢の新生児の予測のために、受信機操作特性曲線が構築されました。双子1と2の場合、相対誤差またはパーセンテージ誤差は次のように計算されました:(出生体重 - 超音波推定胎児重量(または磁気共鳴測定胎児重量)/出生時体重)×100(パーセンテージ)。さらに、超音波推定胎児重量、磁気共鳴測定胎児重量、および出生級の不一致は、100倍(推定胎児の推定推定胎児重量)/より大きな推定胎児体重として計算されました。超音波を推定する胎児体重の不一致と出生級の不一致は、線形回帰分析とピアソンの相関係数を使用して相関しました。同じことが、磁気共鳴を推定する胎児の体重と出生老年度の不一致との間で行われました。データを比較するために、χ2、McNemarテスト、スチューデントTテスト、およびWilcoxon署名ランクテストを必要に応じて使用しました。Fisher R-to-Z変換を使用して、相関係数を比較しました。 結果:超音波推定胎児体重のバイアスと95%の一致の制限は、2.99(-19.17%から25.15%)および磁気共鳴を推定する胎児体重0.63(-9.41%から10.67%)です。超音波推定胎児体重と比較して、磁気共鳴を推定する胎児重量と実際の出生級の間で一致の制限が良好でした。66人の新生児のうち、27人(40.9%)は10才か以下の重量であり、5才以下の21人(31.8%)でした。出生時重量の予測のための受信機操作特性曲線の下の領域は、出生前超音波による10剤以下を0.895(p <.001; SE、0.049)、磁気共鳴画像による0.946(p <.001; SE、0.024)でした。受信機を操作する特性曲線のペアワイズ比較は、受信機操作特性曲線の下の領域間に有意差を示しました(差、0.087、p = .049; SE、0.044)。超音波推定胎児体重の相対誤差は6.8%であり、磁気共鳴を推定する胎児重量、3.2%(p <.001)。超音波推定胎児重量を使用すると、胎児の37.9%(66の25)が実際の出生時体重の±10%の範囲外で推定されましたが、磁気共振胎児体重(p <.001)で6.1%(66の4)に低下しました。超音波推定胎児体重の不一致と出生級の不一致は、線形方程式に従って有意に相関していました:超音波推定胎児体重の不一致= 0.03+ 0.91×出生体重(r = 0.75; p <.001);ただし、相関は磁気共鳴画像法でより良くなりました:磁気共鳴を推定する胎児体重の不一致= 0.02+ 0.81×出生時体重(r = 0.87; p <.001)。 結論:双子の妊娠では、分娩の直前に実行される磁気共振胎児体重がより正確であり、超音波及ぼす胎児体重よりも少量の新生児が大幅に優れていると予測します。超音波と比較して、磁気共鳴画像法では、出生老年度の不一致の予測が優れています。

BACKGROUND: During prenatal follow-up of twin pregnancies, accurate identification of birthweight and birthweight discordance is important to identify the high-risk group and plan perinatal care. Unfortunately, prenatal evaluation of birthweight discordance by 2-dimensional ultrasound has been far from optimal. OBJECTIVE: The objective of the study was to prospectively compare estimates of fetal weight based on 2-dimensional ultrasound (ultrasound-estimated fetal weight) and magnetic resonance imaging (magnetic resonance-estimated fetal weight) with actual birthweight in women carrying twin pregnancies. STUDY DESIGN: Written informed consent was obtained for this ethics committee-approved study. Between September 2011 and December 2015 and within 48 hours before delivery, ultrasound-estimated fetal weight and magnetic resonance-estimated fetal weight were conducted in 66 fetuses deriving from twin pregnancies at 34.3-39.0 weeks; gestation. Magnetic resonance-estimated fetal weight derived from manual measurement of fetal body volume. Comparison of magnetic resonance-estimated fetal weight and ultrasound-estimated fetal weight measurements vs birthweight was performed by calculating parameters as described by Bland and Altman. Receiver-operating characteristic curves were constructed for the prediction of small-for-gestational-age neonates using magnetic resonance-estimated fetal weight and ultrasound-estimated fetal weight. For twins 1 and 2 separately, the relative error or percentage error was calculated as follows: (birthweight - ultrasound-estimated fetal weight (or magnetic resonance-estimated fetal weight)/birthweight) × 100 (percentage). Furthermore, ultrasound-estimated fetal weight, magnetic resonance-estimated fetal weight, and birthweight discordance were calculated as 100 × (larger estimated fetal weight-smaller estimated fetal weight)/larger estimated fetal weight. The ultrasound-estimated fetal weight discordance and the birthweight discordance were correlated using linear regression analysis and Pearson's correlation coefficient. The same was done between the magnetic resonance-estimated fetal weight and birthweight discordance. To compare data, the χ2, McNemar test, Student t test, and Wilcoxon signed rank test were used as appropriate. We used the Fisher r-to-z transformation to compare correlation coefficients. RESULTS: The bias and the 95% limits of agreement of ultrasound-estimated fetal weight are 2.99 (-19.17% to 25.15%) and magnetic resonance-estimated fetal weight 0.63 (-9.41% to 10.67%). Limits of agreement were better between magnetic resonance-estimated fetal weight and actual birthweight as compared with the ultrasound-estimated fetal weight. Of the 66 newborns, 27 (40.9%) were of weight of the 10th centile or less and 21 (31.8%) of the fifth centile or less. The area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve for prediction of birthweight the 10th centile or less by prenatal ultrasound was 0.895 (P < .001; SE, 0.049), and by magnetic resonance imaging it was 0.946 (P < .001; SE, 0.024). Pairwise comparison of receiver-operating characteristic curves showed a significant difference between the areas under the receiver-operating characteristic curves (difference, 0.087, P = .049; SE, 0.044). The relative error for ultrasound-estimated fetal weight was 6.8% and by magnetic resonance-estimated fetal weight, 3.2% (P < .001). When using ultrasound-estimated fetal weight, 37.9% of fetuses (25 of 66) were estimated outside the range of ±10% of the actual birthweight, whereas this dropped to 6.1% (4 of 66) with magnetic resonance-estimated fetal weight (P < .001). The ultrasound-estimated fetal weight discordance and the birthweight discordance correlated significantly following the linear equation: ultrasound-estimated fetal weight discordance = 0.03 + 0.91 × birthweight (r = 0.75; P < .001); however, the correlation was better with magnetic resonance imaging: magnetic resonance-estimated fetal weight discordance = 0.02 + 0.81 × birthweight (r = 0.87; P < .001). CONCLUSION: In twin pregnancies, magnetic resonance-estimated fetal weight performed immediately prior to delivery is more accurate and predicts small-for-gestational-age neonates significantly better than ultrasound-estimated fetal weight. Prediction of birthweight discordance is better with magnetic resonance imaging as compared with ultrasound.

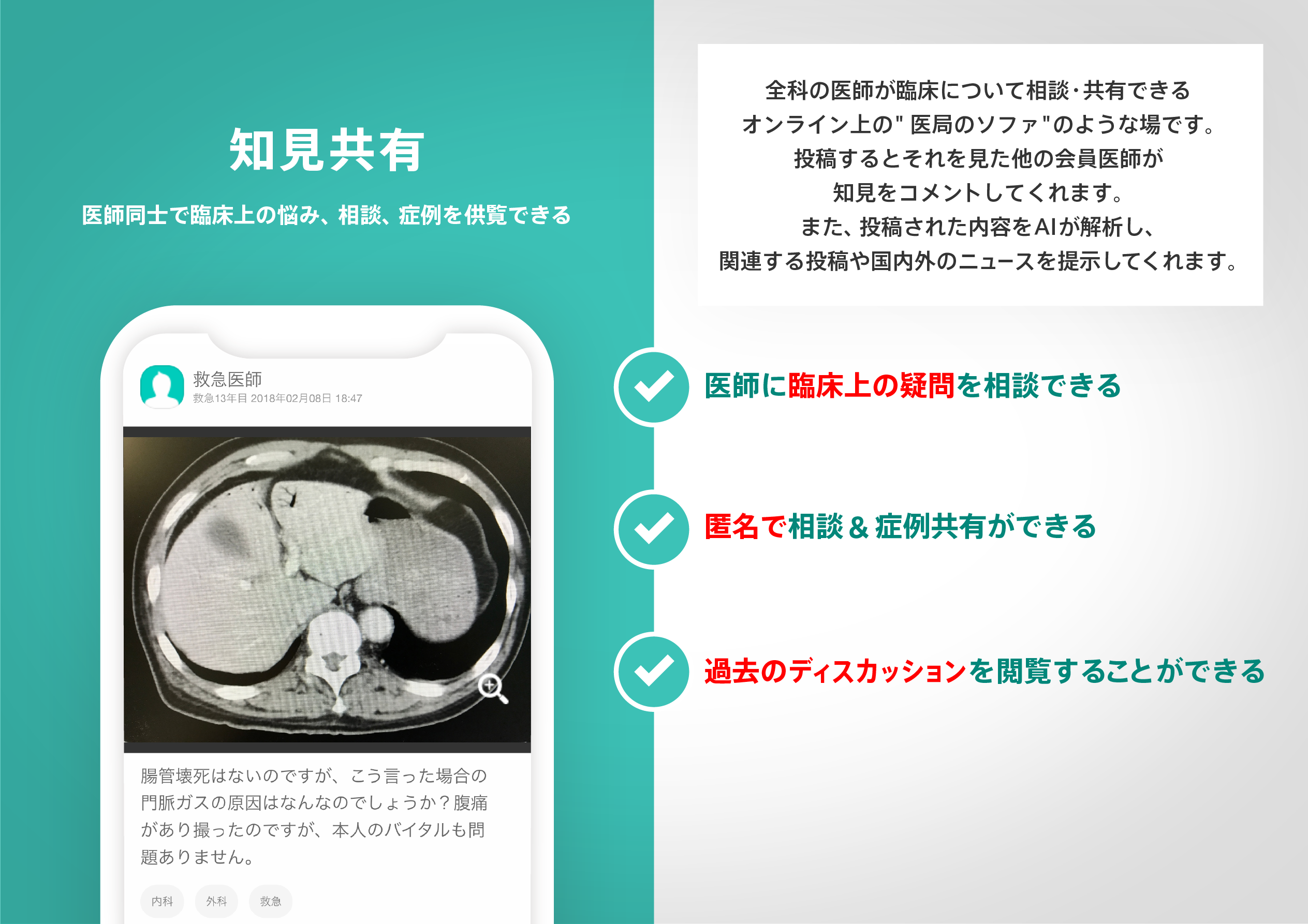

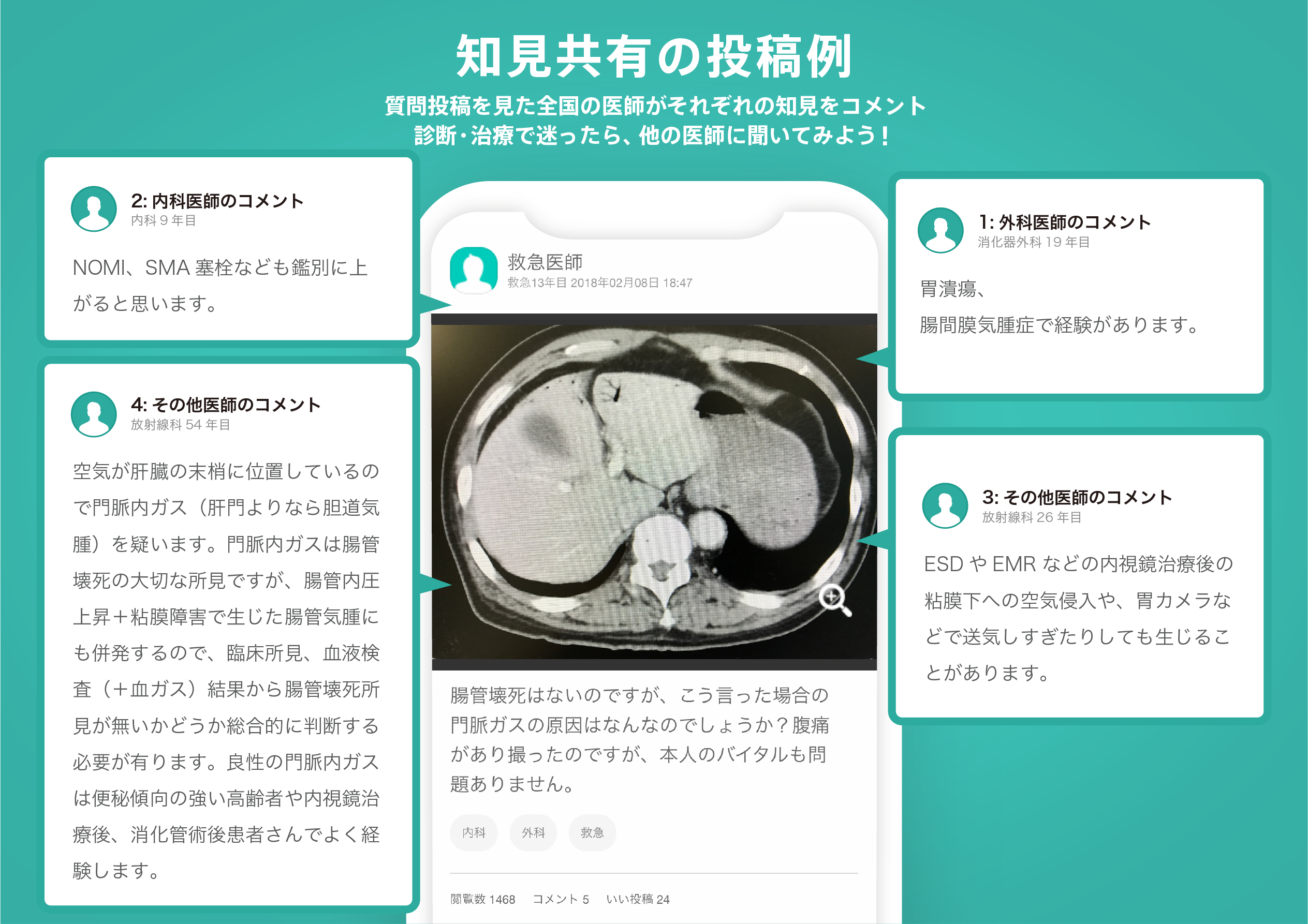

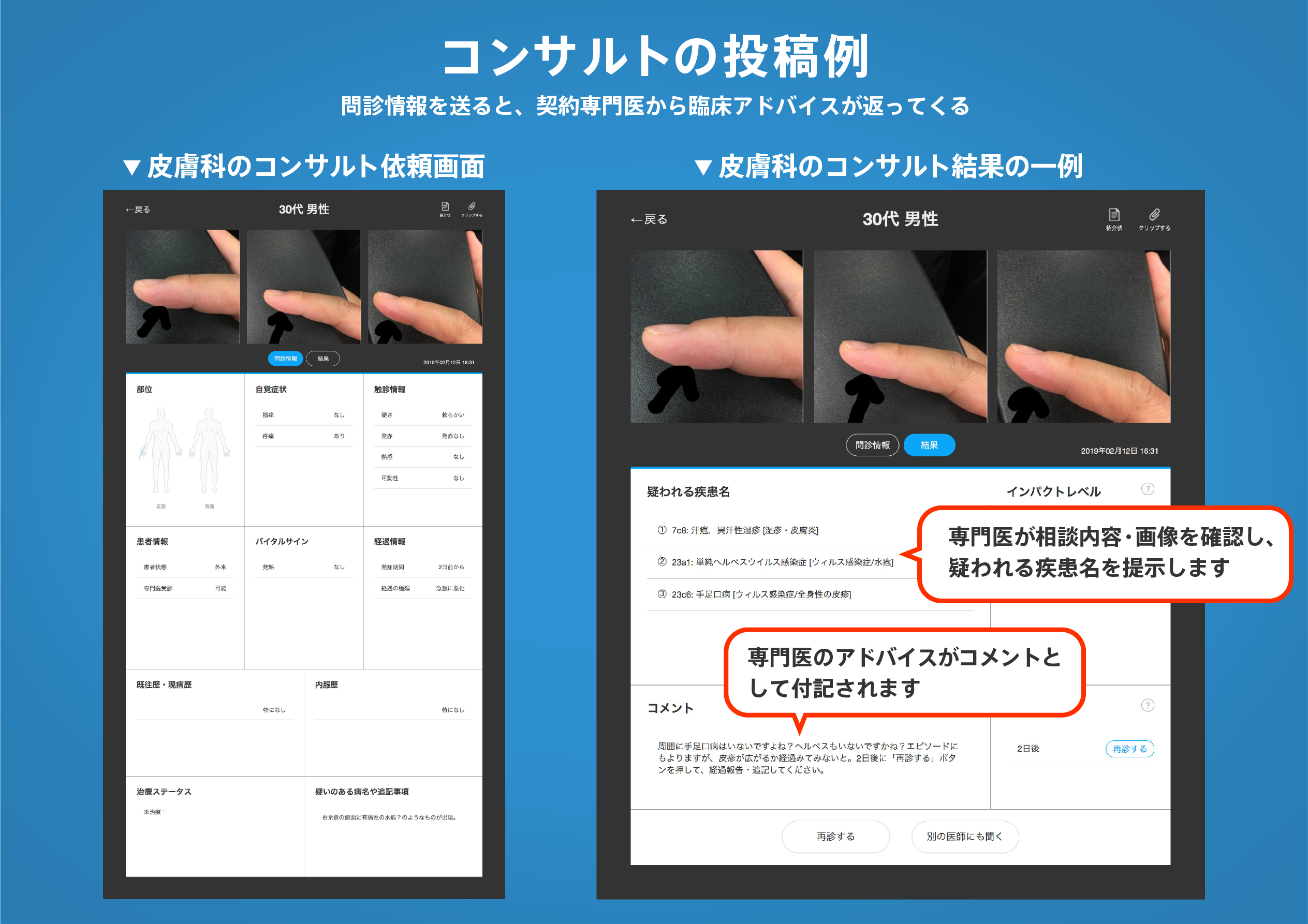

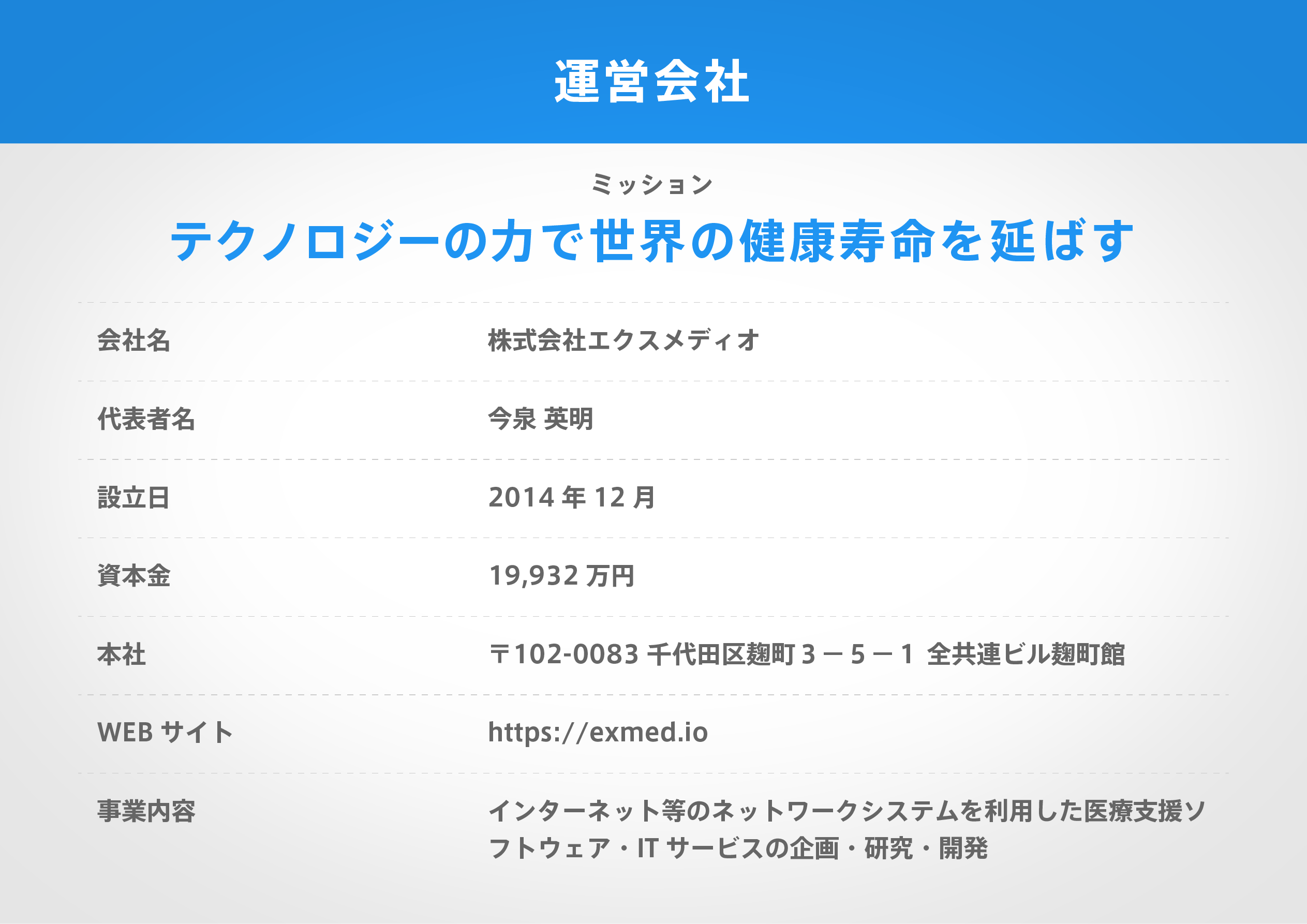

医師のための臨床サポートサービス

ヒポクラ x マイナビのご紹介

無料会員登録していただくと、さらに便利で効率的な検索が可能になります。