著名医師による解説が無料で読めます

すると翻訳の精度が向上します

目的:この研究の目的は、DSM-によって定義されたPTSDの非人格化/解離分離サブタイプの証拠を評価することにより、外傷後青年の臨床サンプルにおける心的外傷後ストレス障害(PTSD)の共起と解離を調べることでした。5そして、より広範な解離症状を調べます。 方法:全国の子どもの外傷性ストレスネットワークコアデータセットからの治療を求める、外傷を負う青年期のサンプル(n = 3,081)を使用して、研究目標を達成しました。PTSD/解離の2つのモデルは、潜在的なクラス分析を使用して推定されました。1つは2つの解離症状があり、もう1つは解離症状が10つありました。モデル選択後、各モデル内のグループを人口統計、外傷特性、および精神病理学と比較しました。 結果:非人格化/解釈モデルであるモデルAには、5つのクラスがありました。解離性サブタイプ/高PTSD。高PTSD;不安な覚醒;不快な覚醒;低症状/参照クラス。拡張された解離モデルであるモデルBは、解離性健忘症と分離した覚醒を特徴とする追加のクラスを特定しました。 結論:これらの2つのモデルは、PTSDと解離の具体的な方法に関する新しい情報を提供し、成人と思春期の外傷症状の発現の違いを照らします。PTSDの解離性サブタイプは、思春期のPTSDのみと区別できますが、思春期の外傷性ストレス反応を完全に特徴付けるには、より広範な解離症状を評価する必要があります。

目的:この研究の目的は、DSM-によって定義されたPTSDの非人格化/解離分離サブタイプの証拠を評価することにより、外傷後青年の臨床サンプルにおける心的外傷後ストレス障害(PTSD)の共起と解離を調べることでした。5そして、より広範な解離症状を調べます。 方法:全国の子どもの外傷性ストレスネットワークコアデータセットからの治療を求める、外傷を負う青年期のサンプル(n = 3,081)を使用して、研究目標を達成しました。PTSD/解離の2つのモデルは、潜在的なクラス分析を使用して推定されました。1つは2つの解離症状があり、もう1つは解離症状が10つありました。モデル選択後、各モデル内のグループを人口統計、外傷特性、および精神病理学と比較しました。 結果:非人格化/解釈モデルであるモデルAには、5つのクラスがありました。解離性サブタイプ/高PTSD。高PTSD;不安な覚醒;不快な覚醒;低症状/参照クラス。拡張された解離モデルであるモデルBは、解離性健忘症と分離した覚醒を特徴とする追加のクラスを特定しました。 結論:これらの2つのモデルは、PTSDと解離の具体的な方法に関する新しい情報を提供し、成人と思春期の外傷症状の発現の違いを照らします。PTSDの解離性サブタイプは、思春期のPTSDのみと区別できますが、思春期の外傷性ストレス反応を完全に特徴付けるには、より広範な解離症状を評価する必要があります。

OBJECTIVE: The purpose of this study was to examine the co-occurrence of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and dissociation in a clinical sample of trauma-exposed adolescents by evaluating evidence for the depersonalization/derealization dissociative subtype of PTSD as defined by the DSM-5 and then examining a broader set of dissociation symptoms. METHOD: A sample of treatment-seeking, trauma-exposed adolescents 12 to 16 years old (N = 3,081) from the National Child Traumatic Stress Network Core Data Set was used to meet the study objectives. Two models of PTSD/dissociation co-occurrence were estimated using latent class analysis, one with 2 dissociation symptoms and the other with 10 dissociation symptoms. After model selection, groups within each model were compared on demographics, trauma characteristics, and psychopathology. RESULTS: Model A, the depersonalization/derealization model, had 5 classes: dissociative subtype/high PTSD; high PTSD; anxious arousal; dysphoric arousal; and a low symptom/reference class. Model B, the expanded dissociation model, identified an additional class characterized by dissociative amnesia and detached arousal. CONCLUSION: These 2 models provide new information about the specific ways PTSD and dissociation co-occur and illuminate some differences between adult and adolescent trauma symptom expression. A dissociative subtype of PTSD can be distinguished from PTSD alone in adolescents, but assessing a wider range of dissociative symptoms is needed to fully characterize adolescent traumatic stress responses.

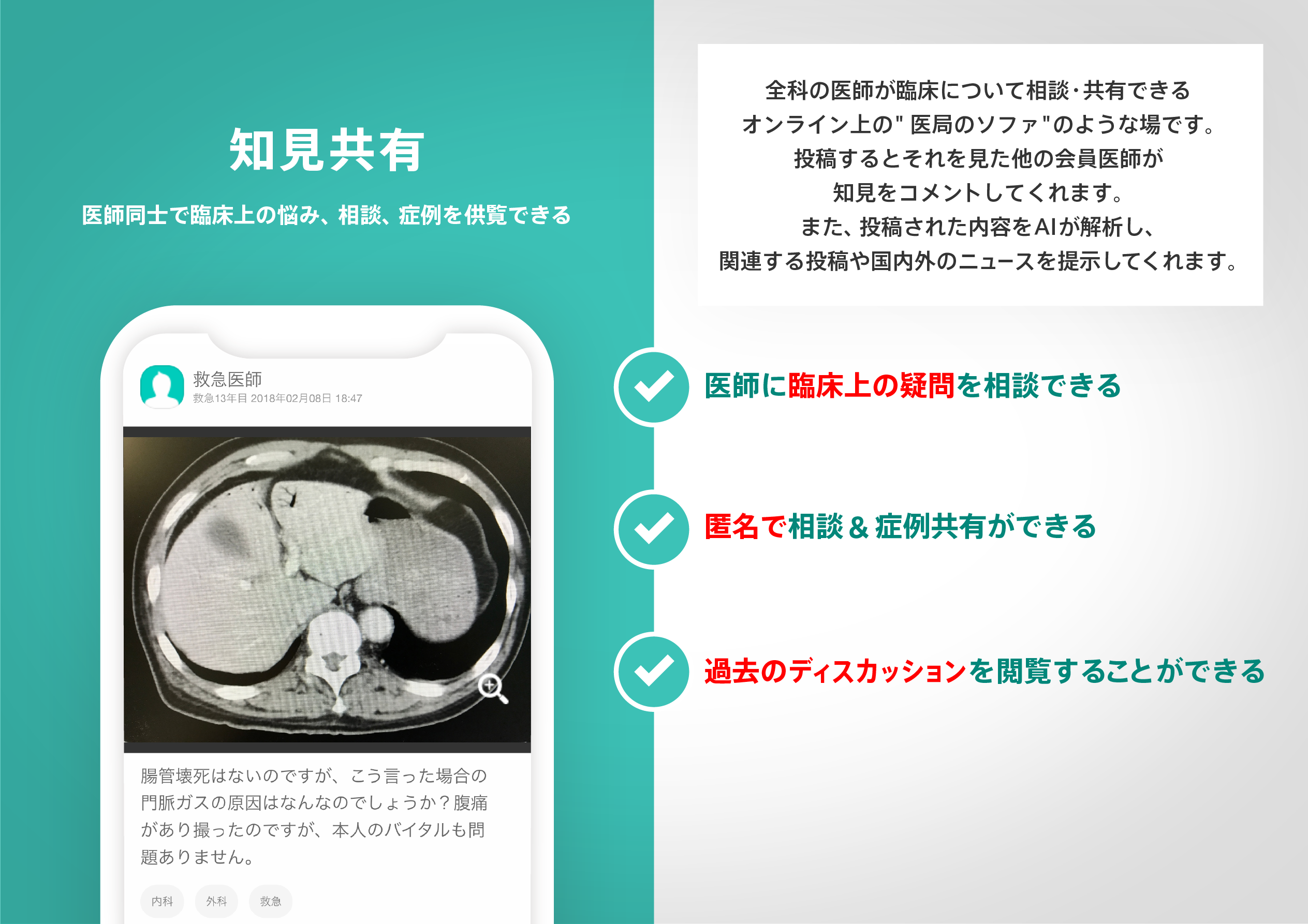

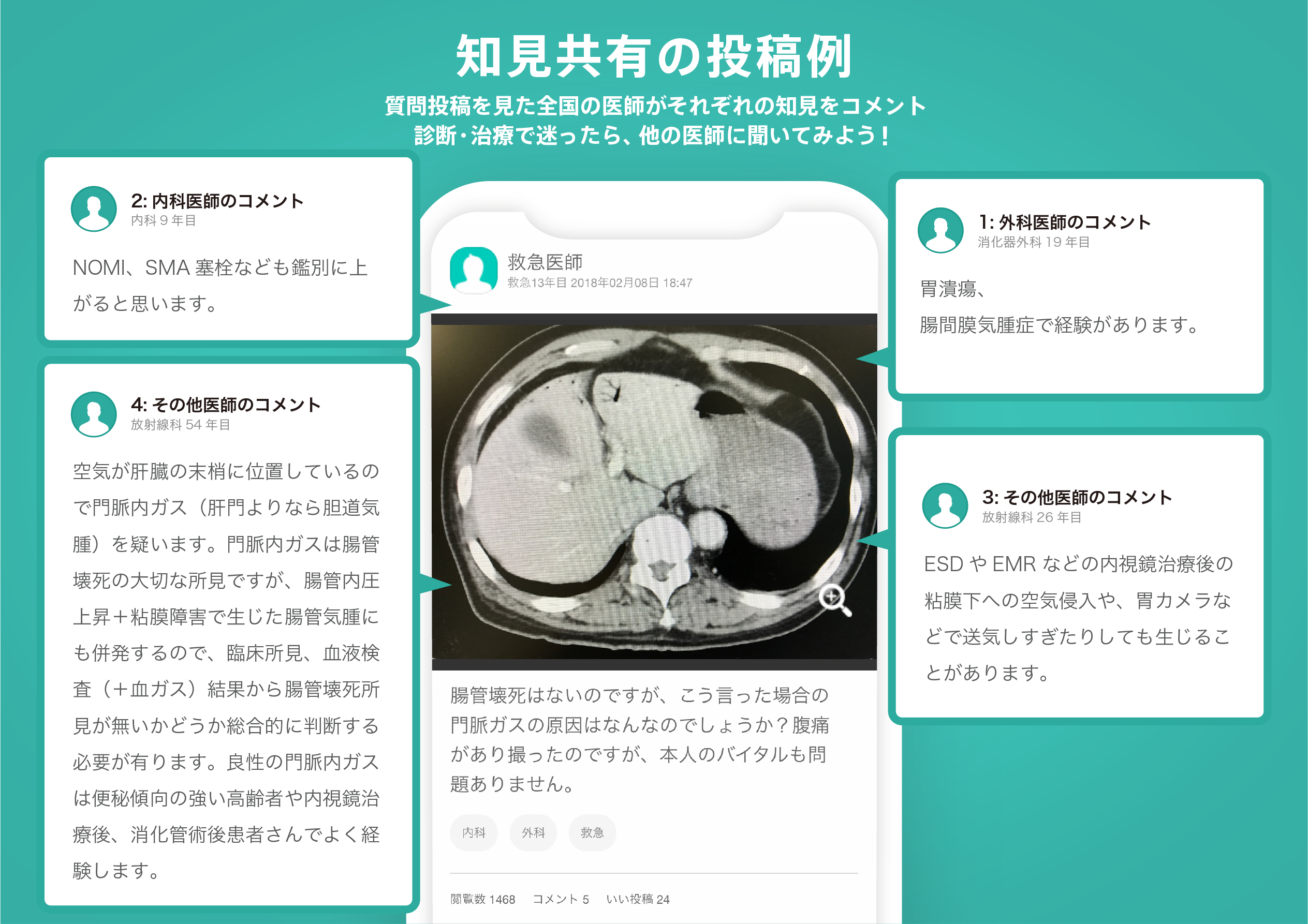

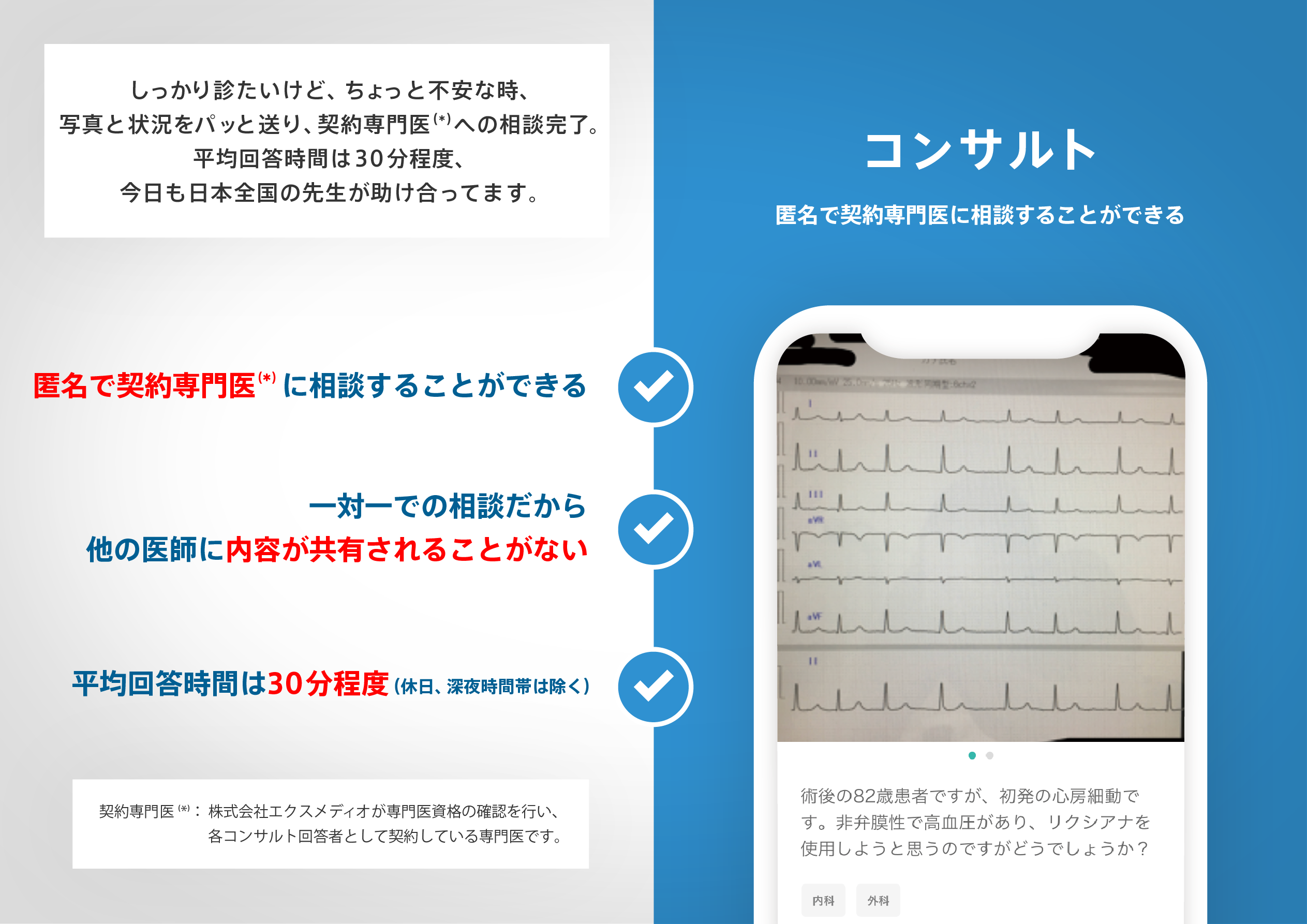

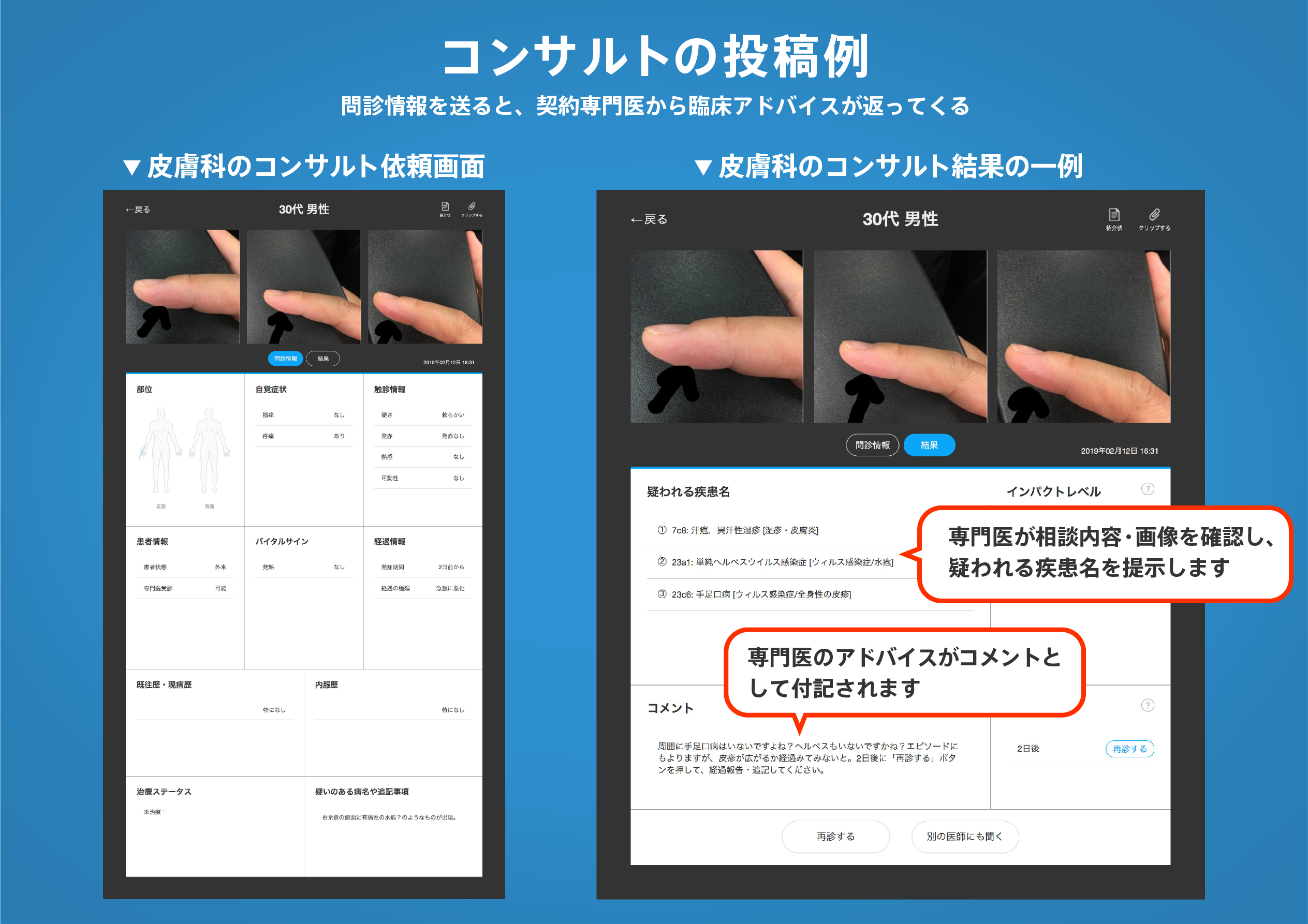

医師のための臨床サポートサービス

ヒポクラ x マイナビのご紹介

無料会員登録していただくと、さらに便利で効率的な検索が可能になります。