著名医師による解説が無料で読めます

すると翻訳の精度が向上します

潜水医学において、バブル誘発性気圧障害の命名法ほど混乱を招く問題はほとんどありません。 1980 年代後半以前は、減圧中または減圧後に溶解した不活性ガスから気泡が形成された結果として生じると推定される症状に対して、「減圧症」(DCS) という診断が行われていました。これらの気泡は、組織内で形成されることが知られており、静脈血にも現れることが知られていました (おそらく組織の毛細血管で形成された後)。 2 番目の診断、'動脈ガス塞栓症' (AGE) は、肺圧外傷の結果として気泡が動脈循環に直接導入されたときに発生すると推定される症状のために呼び出されました。このアプローチは、根底にある病態生理学は通常、結果として生じる症状の性質とテンポから推測できるという仮定に基づいていました。 DCS はよりゆっくりとより進行性の発症を示すと考えられ、症状は変幻自在 (痛み、発疹、感覚異常、皮下腫脹、および神経学的症状を含む) であり、神経学的症状は主に脊髄または内耳の関与に起因していました。対照的に、AGEはより急激な発症を示すと考えられ(多くの場合、表面に現れた直後)、主な症状は脳への関与を示唆する脳卒中のような局所的な神経学的障害でした. 1989 年に、大きな持続性 (「特許」) の卵円孔 (PFO) と深刻な神経学的 DCS との関連が 2 つのグループによって個別に報告され、その後、複数の研究によって神経学的、内耳、および皮膚の DCS が裏付けられました。この設定における PFO の想定される病態生理学的役割は、静脈血中の不活性ガスから形成された気泡が肺循環で除去されるのを回避し、動脈循環に入ることを可能にすることでした。これらの気泡は、周囲の組織からの過飽和不活性ガスの内部拡散により、脆弱な標的組織の微小循環に移動する可能性があります。いくつかの形態の DCS における重要な害のベクトルとしての静脈気泡の「動脈化」のこの出現は、従来の「DCS/AGE」用語の使用に対する挑戦をもたらしました。潜水後の脳症状の非常に早期の発症は、肺の圧外傷によって導入された動脈の泡だけでなく、PFOを横切って動脈循環に入る静脈の泡によっても説明できることが示唆されました。さらに、静脈の気泡が動脈循環に入ると、技術的には「動脈ガス塞栓」になります。したがって、肺圧外傷による動脈ガス塞栓と混同されます。多くのコメンテーターにとって、2 つの障害を区別するのが難しく、機械的プロセスが共通している場合に、特定の病態生理学を示唆する診断ラベル (DCS と AGE) を使用することはほとんど意味がありませんでした。 1991 年の UHMS ワークショップで導き出された別のアプローチは、特定の病態生理学を暗示する命名法から、DCS と AGE の両方をまとめて「減圧症」(DCI) というラベルの下にまとめた記述システムに移行することでした。このシステムを使用して、関係する器官系と症状の進行を説明する用語が適用されました。たとえば、ダイビング後に上腕の痛みが悪化したダイバーは、「進行性筋骨格 DCI」に苦しんでいる可能性があります。また、浮上してすぐに意識を失ったが、数分後に意識を取り戻したダイバーは、「脳の DCI の緩和」に苦しんでいると見なされます。このように症例を分類することは、臨床レベルでかなり理にかなっています。特に、潜在的に重複する DCS と AGE の症状は、再圧迫治療に異なるアプローチを必要としないという新たなコンセンサスがあったことを考えると。泡によって誘発された障害性疾患のこの記述的な分類は、そのアプリケーションの意図されたニュアンスのユーザーによる完全な評価が常にあるわけではありませんが、コミュニティで実質的な牽引力を獲得しました.実際、DCS と DCI という用語が同じ意味で使用されることは、時間の経過とともにますます一般的になりました。たとえば、DCIという用語を使用して、溶存ガスからの気泡形成の結果を具体的に推測する著者。これは、DCI 用語の欠点の 1 つを浮き彫りにします。つまり、障害の性質がわかっている場合、または溶解ガスまたは肺圧外傷による気泡形成を議論する特定の意図がある場合、理論的または実験的レベルで dysbaric 疾患を議論すると混乱します。 . DCI 用語を採用するための主要な推進要因の 1 つとして、DCS と AGE のメカニズムと症状の間の混同の可能性については、さらに議論する価値があります。静脈の気泡が PFO を通過して動脈血に入る場合、結果として生じる症状はすべて「AGE」の徴候と見なされるべきであると示唆したくなります。ただし、気泡が他の場所に分布したという理由だけで、主要な病態生理学的イベント (不活性ガスからの気泡形成によって引き起こされる DCS) の名前を変更することにはほとんど意味がないようです。特に、完全に異なる一次事象 (肺圧外傷による気泡形成) を一般的に推測する名前を使用します。さらに、これらの 2 つのプロセスを区別することは、これまで信じられていたほど難しくない可能性があることを示唆する根拠があります。静脈の不活性ガスの気泡は小さく、PFO テスト中に気泡コントラストとして使用されるものと同様のサイズ分布です。気泡造影心エコー検査を使用して何千人ものダイバー (および他の患者) を PFO について検査してきた数十年の経験から、強い陽性 (つまり、気泡の大きなシャワーが動脈循環に入る) の場合でも、あらゆる種類の症状が非常にまれであることが示されています。エバネッセント視覚症状または脳症状の散発的な報告がありますが、(この著者の知る限りでは)医原性に導入された大きな動脈気泡または肺圧外傷によって引き起こされる可能性がある局所性または多発性脳梗塞の報告はありません。 PFO 検査の文脈では、脳は不活性ガスで過飽和ではなく (小さな動脈の気泡が成長する原因となる可能性があります)、そのような「速い組織」ではなく、ダイビング後でもありそうにないと主張する人もいるでしょう。したがって、潜水後に PFO を横切る小さな不活性気泡の持続的なシャワーは、潜水後の一時的な視覚症状または実行障害症候群のもっともらしい原因として訴える一方で、浮上後早期に発生する劇的な脳卒中のような事象の原因となる可能性は低い. Bennett と Elliott の最終版では、用語の難問に対する 1 つの編集アプローチは、溶解した不活性ガスまたは肺圧外傷からの気泡形成の病態生理学および症状に特に言及する場合、伝統的な用語 (DCS および AGE) を利用することであることが示唆されました。 、総称が有用である場合、または病態生理学についてあいまいな場合、または区別を試みる必要がない場合に個々の患者について議論する場合に、臨床的議論で記述的(DCI)用語を使用します。 Diving and Hyperbaric Medicine も同様のアプローチを推奨しています。ジャーナルは、気泡誘発性の障害性疾患の用語に関連して厳しい「ルール」を作成または適用しようとすることに消極的ですが、「動脈ガス塞栓症」という用語を使用して、血管を横切る静脈の不活性ガス気泡を特徴付けるのを強く思いとどまらせます。 PFO などの右から左へのシャント。溶解した不活性ガスからの気泡形成の病態生理学的結果は、減圧症 (DCS) と見なされるべきです。著者は上記の問題を認識しており、これらの考慮事項を反映し、原稿の状況に最も適した用語を採用しようとすることが期待されています.

潜水医学において、バブル誘発性気圧障害の命名法ほど混乱を招く問題はほとんどありません。 1980 年代後半以前は、減圧中または減圧後に溶解した不活性ガスから気泡が形成された結果として生じると推定される症状に対して、「減圧症」(DCS) という診断が行われていました。これらの気泡は、組織内で形成されることが知られており、静脈血にも現れることが知られていました (おそらく組織の毛細血管で形成された後)。 2 番目の診断、'動脈ガス塞栓症' (AGE) は、肺圧外傷の結果として気泡が動脈循環に直接導入されたときに発生すると推定される症状のために呼び出されました。このアプローチは、根底にある病態生理学は通常、結果として生じる症状の性質とテンポから推測できるという仮定に基づいていました。 DCS はよりゆっくりとより進行性の発症を示すと考えられ、症状は変幻自在 (痛み、発疹、感覚異常、皮下腫脹、および神経学的症状を含む) であり、神経学的症状は主に脊髄または内耳の関与に起因していました。対照的に、AGEはより急激な発症を示すと考えられ(多くの場合、表面に現れた直後)、主な症状は脳への関与を示唆する脳卒中のような局所的な神経学的障害でした. 1989 年に、大きな持続性 (「特許」) の卵円孔 (PFO) と深刻な神経学的 DCS との関連が 2 つのグループによって個別に報告され、その後、複数の研究によって神経学的、内耳、および皮膚の DCS が裏付けられました。この設定における PFO の想定される病態生理学的役割は、静脈血中の不活性ガスから形成された気泡が肺循環で除去されるのを回避し、動脈循環に入ることを可能にすることでした。これらの気泡は、周囲の組織からの過飽和不活性ガスの内部拡散により、脆弱な標的組織の微小循環に移動する可能性があります。いくつかの形態の DCS における重要な害のベクトルとしての静脈気泡の「動脈化」のこの出現は、従来の「DCS/AGE」用語の使用に対する挑戦をもたらしました。潜水後の脳症状の非常に早期の発症は、肺の圧外傷によって導入された動脈の泡だけでなく、PFOを横切って動脈循環に入る静脈の泡によっても説明できることが示唆されました。さらに、静脈の気泡が動脈循環に入ると、技術的には「動脈ガス塞栓」になります。したがって、肺圧外傷による動脈ガス塞栓と混同されます。多くのコメンテーターにとって、2 つの障害を区別するのが難しく、機械的プロセスが共通している場合に、特定の病態生理学を示唆する診断ラベル (DCS と AGE) を使用することはほとんど意味がありませんでした。 1991 年の UHMS ワークショップで導き出された別のアプローチは、特定の病態生理学を暗示する命名法から、DCS と AGE の両方をまとめて「減圧症」(DCI) というラベルの下にまとめた記述システムに移行することでした。このシステムを使用して、関係する器官系と症状の進行を説明する用語が適用されました。たとえば、ダイビング後に上腕の痛みが悪化したダイバーは、「進行性筋骨格 DCI」に苦しんでいる可能性があります。また、浮上してすぐに意識を失ったが、数分後に意識を取り戻したダイバーは、「脳の DCI の緩和」に苦しんでいると見なされます。このように症例を分類することは、臨床レベルでかなり理にかなっています。特に、潜在的に重複する DCS と AGE の症状は、再圧迫治療に異なるアプローチを必要としないという新たなコンセンサスがあったことを考えると。泡によって誘発された障害性疾患のこの記述的な分類は、そのアプリケーションの意図されたニュアンスのユーザーによる完全な評価が常にあるわけではありませんが、コミュニティで実質的な牽引力を獲得しました.実際、DCS と DCI という用語が同じ意味で使用されることは、時間の経過とともにますます一般的になりました。たとえば、DCIという用語を使用して、溶存ガスからの気泡形成の結果を具体的に推測する著者。これは、DCI 用語の欠点の 1 つを浮き彫りにします。つまり、障害の性質がわかっている場合、または溶解ガスまたは肺圧外傷による気泡形成を議論する特定の意図がある場合、理論的または実験的レベルで dysbaric 疾患を議論すると混乱します。 . DCI 用語を採用するための主要な推進要因の 1 つとして、DCS と AGE のメカニズムと症状の間の混同の可能性については、さらに議論する価値があります。静脈の気泡が PFO を通過して動脈血に入る場合、結果として生じる症状はすべて「AGE」の徴候と見なされるべきであると示唆したくなります。ただし、気泡が他の場所に分布したという理由だけで、主要な病態生理学的イベント (不活性ガスからの気泡形成によって引き起こされる DCS) の名前を変更することにはほとんど意味がないようです。特に、完全に異なる一次事象 (肺圧外傷による気泡形成) を一般的に推測する名前を使用します。さらに、これらの 2 つのプロセスを区別することは、これまで信じられていたほど難しくない可能性があることを示唆する根拠があります。静脈の不活性ガスの気泡は小さく、PFO テスト中に気泡コントラストとして使用されるものと同様のサイズ分布です。気泡造影心エコー検査を使用して何千人ものダイバー (および他の患者) を PFO について検査してきた数十年の経験から、強い陽性 (つまり、気泡の大きなシャワーが動脈循環に入る) の場合でも、あらゆる種類の症状が非常にまれであることが示されています。エバネッセント視覚症状または脳症状の散発的な報告がありますが、(この著者の知る限りでは)医原性に導入された大きな動脈気泡または肺圧外傷によって引き起こされる可能性がある局所性または多発性脳梗塞の報告はありません。 PFO 検査の文脈では、脳は不活性ガスで過飽和ではなく (小さな動脈の気泡が成長する原因となる可能性があります)、そのような「速い組織」ではなく、ダイビング後でもありそうにないと主張する人もいるでしょう。したがって、潜水後に PFO を横切る小さな不活性気泡の持続的なシャワーは、潜水後の一時的な視覚症状または実行障害症候群のもっともらしい原因として訴える一方で、浮上後早期に発生する劇的な脳卒中のような事象の原因となる可能性は低い. Bennett と Elliott の最終版では、用語の難問に対する 1 つの編集アプローチは、溶解した不活性ガスまたは肺圧外傷からの気泡形成の病態生理学および症状に特に言及する場合、伝統的な用語 (DCS および AGE) を利用することであることが示唆されました。 、総称が有用である場合、または病態生理学についてあいまいな場合、または区別を試みる必要がない場合に個々の患者について議論する場合に、臨床的議論で記述的(DCI)用語を使用します。 Diving and Hyperbaric Medicine も同様のアプローチを推奨しています。ジャーナルは、気泡誘発性の障害性疾患の用語に関連して厳しい「ルール」を作成または適用しようとすることに消極的ですが、「動脈ガス塞栓症」という用語を使用して、血管を横切る静脈の不活性ガス気泡を特徴付けるのを強く思いとどまらせます。 PFO などの右から左へのシャント。溶解した不活性ガスからの気泡形成の病態生理学的結果は、減圧症 (DCS) と見なされるべきです。著者は上記の問題を認識しており、これらの考慮事項を反映し、原稿の状況に最も適した用語を採用しようとすることが期待されています.

There are few issues that generate as much confusion in diving medicine as the nomenclature of bubble-induced dysbaric disease. Prior to the late 1980s, the diagnosis 'decompression sickness' (DCS) was invoked for symptoms presumed to arise as a consequence of bubble formation from dissolved inert gas during or after decompression. These bubbles were known to form within tissues, and also to appear in the venous blood (presumably after forming in tissue capillaries). A second diagnosis, 'arterial gas embolism' (AGE) was invoked for symptoms presumed to arise when bubbles were introduced directly to the arterial circulation as a consequence of pulmonary barotrauma. This approach was predicated on an assumption that the underlying pathophysiology could usually be inferred from the nature and tempo of resulting symptoms. DCS was considered to exhibit a slower more progressive onset, symptoms were protean (including pain, rash, paraesthesias, subcutaneous swelling, and neurological symptoms), and the neurological manifestations were mainly attributable to spinal cord or inner ear involvement. In contrast, AGE was considered to exhibit a more precipitous onset (often immediately on surfacing), and the principal manifestation was stroke-like focal neurological impairment suggestive of cerebral involvement. In 1989 an association between a large persistent ('patent') foramen ovale (PFO) and serious neurological DCS was independently reported by two groups, and subsequently corroborated for neurological, inner ear, and cutaneous DCS by multiple studies. The assumed pathophysiological role of a PFO in this setting was to allow bubbles formed from inert gas in the venous blood to avoid removal in the pulmonary circulation and to enter the arterial circulation. These bubbles could then pass to the microcirculation of vulnerable target tissues where inward diffusion of supersaturated inert gas from the surrounding tissue could cause them to grow. This emergence of 'arterialisation' of venous bubbles as an important vector of harm in some forms of DCS resulted in a challenge to the use of traditional 'DCS/AGE' terminology. It was suggested that very early onset of cerebral symptoms after diving could be explained not only by arterial bubbles introduced by pulmonary barotrauma, but also by venous bubbles crossing a PFO into the arterial circulation. Moreover, once venous bubbles had entered the arterial circulation they were then technically 'arterial gas emboli'; thus creating confusion with arterial gas emboli from pulmonary barotrauma. To many commentators, it made little sense to use diagnostic labels (DCS and AGE) that implied a particular pathophysiology when the two disorders might be difficult to tell apart, and had mechanistic processes in common. An alternative approach derived at a UHMS workshop in 1991 was to shift from nomenclature that implied a particular pathophysiology, to a descriptive system that lumped both DCS and AGE together under the label "decompression illness" (DCI). Using this system, terms to describe the organ system(s) involved and the progression of symptoms were applied. For example, a diver with worsening upper arm pain after a dive could be suffering 'progressive musculoskeletal DCI'; and a diver who lost consciousness immediately on surfacing but regained consciousness minutes later would be considered to be suffering 'remitting cerebral DCI'. Classifying cases in this manner made considerable sense at a clinical level, particularly given that there was an emerging consensus that manifestations of DCS and AGE that potentially overlapped did not require different approaches to recompression treatment. This descriptive classification of bubble-induced dysbaric disease gained substantial traction in the community, though not always with a full appreciation by users of the intended nuances of its application. Indeed, it became increasingly common over time to see the terms DCS and DCI used interchangeably; for example, authors using the term DCI to specifically infer the consequences of bubble formation from dissolved gas. This highlights one of the shortcomings of the DCI terminology: it becomes confusing when discussing dysbaric disease at a theoretical or experimental level when the nature of the insult is known or there is a specific intent to discuss bubble formation either from dissolved gas or from pulmonary barotrauma. The potential for confusion between mechanisms and manifestations of DCS and AGE as one of the principle drivers for adopting the DCI terminology deserves further discussion. It is tempting to suggest that if venous bubbles cross a PFO into the arterial blood then any resulting symptoms should be considered a manifestation of 'AGE'. However, there seems little sense in re-naming the primary pathophysiological event (DCS caused by bubble formation from inert gas) just because the bubbles have distributed elsewhere; especially using a name that commonly infers a completely different primary event (bubble formation from pulmonary barotrauma). Moreover, there are grounds for suggesting that these two processes may not be as difficult to distinguish as previously believed. Venous inert gas bubbles are small, and of a similar size distribution to those used as bubble contrast during PFO testing. Decades of experience in testing thousands of divers (and other patients) for PFO using bubble-contrast echocardiograpy have shown that even when strongly positive (that is, large showers of bubbles enter the arterial circulation), symptoms of any sort are very rare. There are sporadic reports of evanescent visual or cerebral symptoms, but (to this author's knowledge) reports of the focal or multifocal cerebral infarctions that can be caused by large arterial bubbles introduced iatrogenically or by pulmonary barotrauma are lacking. One could argue that in the context of PFO testing the brain is not supersaturated with inert gas (which might cause small arterial bubbles to grow), but being such a 'fast tissue' nor is it likely to be after diving. Thus, while sustained showers of small inert gas bubbles crossing a PFO after diving appeal as a plausible cause of transient visual symptoms or dysexecutive syndromes after diving, they are less likely to be the cause of dramatic stroke-like events occurring early after surfacing. In the final edition of Bennett and Elliott it was suggested that one editorial approach to the terminology conundrum would be to utilise the traditional terminology (DCS and AGE) when referring specifically to the pathophysiology and manifestations of bubble formation from dissolved inert gas or pulmonary barotrauma respectively, and to utilise the descriptive (DCI) terminology in clinical discussions when a collective term is useful, or when discussing individual patients where there is either ambiguity about pathophysiology or no need to attempt a distinction. Diving and Hyperbaric Medicine recommends a similar approach. The journal is reluctant to attempt to generate or apply hard 'rules' in relation to terminology of bubble-induced dysbaric disease, but we strongly discourage use of the term 'arterial gas emboli(ism)' to characterise venous inert gas bubbles that cross a right-to-left shunt such as a PFO. The pathophysiological consequences of bubble formation from dissolved inert gas should be regarded as decompression sickness (DCS). There is an expectation that authors are cognisant of the above issues and attempt to adopt terminology that reflects these considerations and best suits the circumstances of their manuscript.

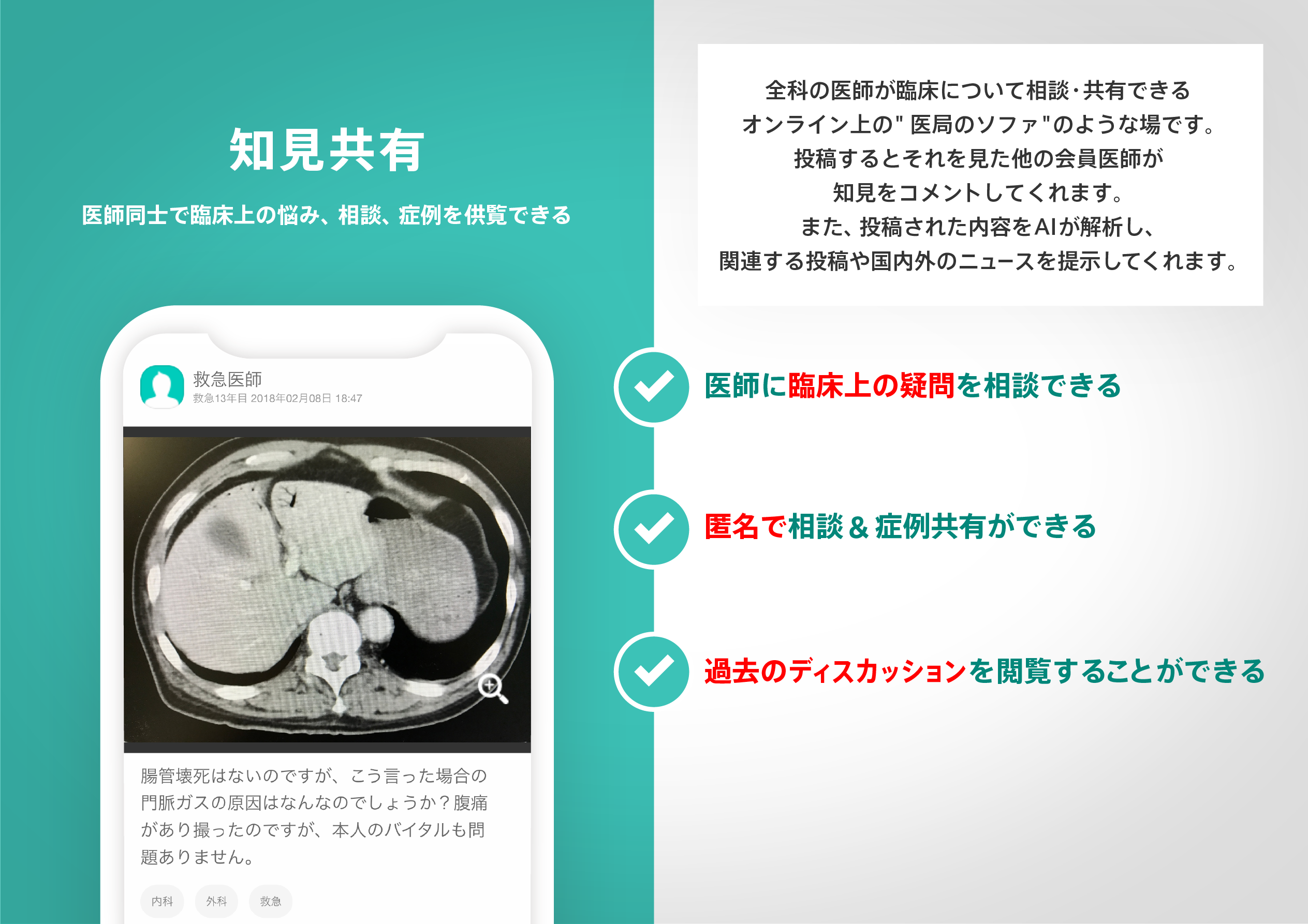

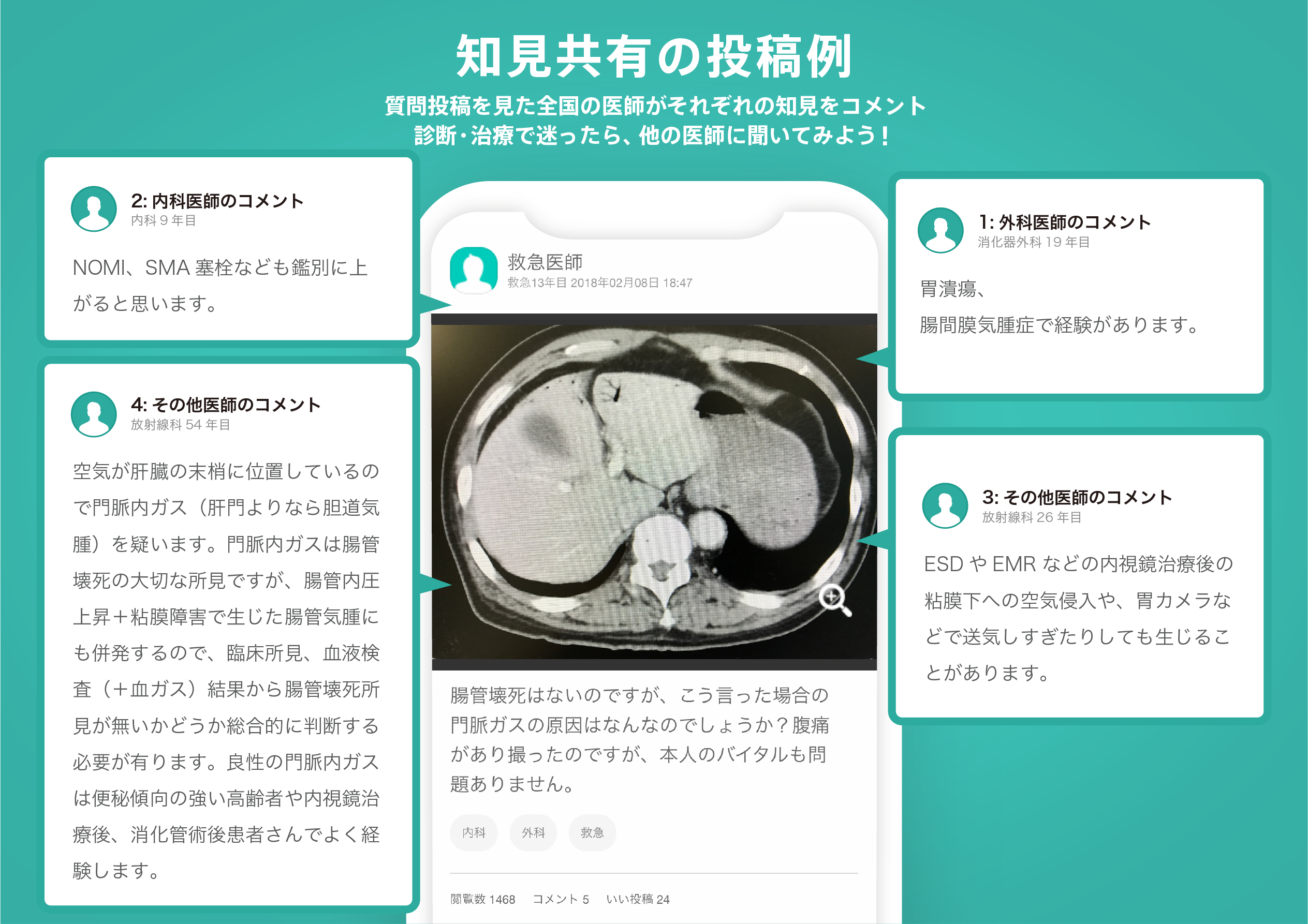

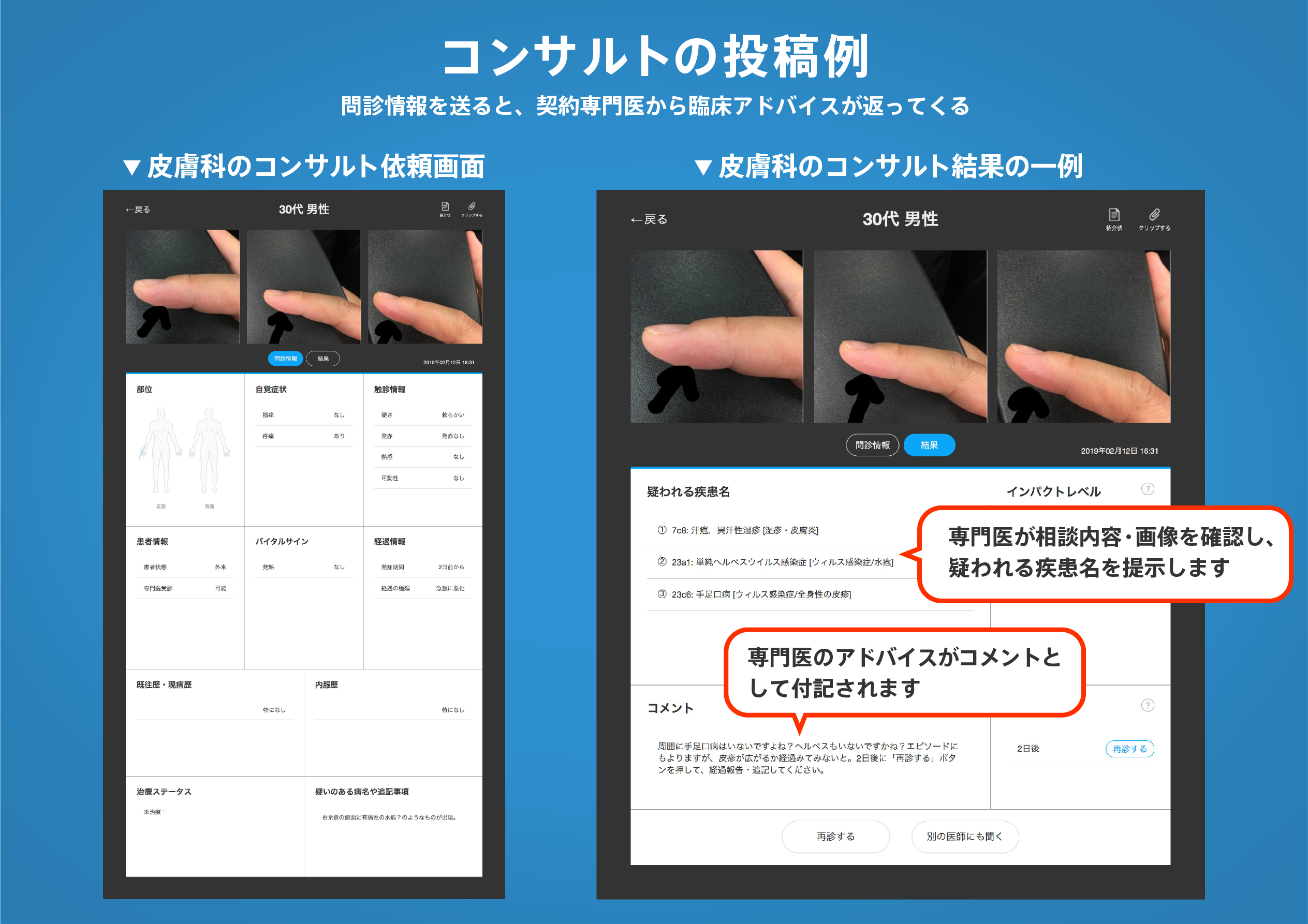

医師のための臨床サポートサービス

ヒポクラ x マイナビのご紹介

無料会員登録していただくと、さらに便利で効率的な検索が可能になります。