著名医師による解説が無料で読めます

すると翻訳の精度が向上します

目的:子供の副次的な経験(ACE)と制限された食品へのアクセスは、摂食障害(EDS)のリスクに関連しています。この研究では、米国の成人の全国的に代表的なサンプルにおける、特に制限された食品アクセスを含むACE、特に制限された食品アクセスを含むACEとの関係を調べました。 方法:参加者は、アルコールおよび関連条件に関する全国疫学調査の36,145人の回答者であり、子供の頃の食物の怠慢に関するデータを提供したIII(NESARC-III)でした。神経性食欲不振症(AN)、神経性過食症(BN)、および強打障害(BED)の有病率は、小児期の怠慢を拒否されたと報告した人のために決定されました。分析は、社会人口学的特性を調整した後の各ED診断の確率(モデル1)を比較し、子供の頃に他のACEと政府の財務支持をさらに調整しました(モデル2)。 結果:幼年期の食物怠慢の歴史を持つAN、BN、およびBEDの有病率の推定値は、それぞれ2.80%(SE = 0.81)、0.60%(SE = 0.21)、および3.50%(SE = 0.82)と0.80%(SE = 0.07)、0.30%(SE = 0.03)、および0.80%(SE = 0.05)が重要ではありません。完全に調整されたモデルでは、AN(AOR = 2.98 [95%CI = 1.56-5.71])およびBED(AOR = 2.95 [95%CI = 1.73-5.03])でED診断を受ける確率は有意に高かった。 結論:小児期の食物の怠慢を経験した人は、ANとベッドのリスクが高くなる可能性があり、リスクの上昇は、子供の頃の他の不利な経験や財政難に合わせて調整した後に存在します。

目的:子供の副次的な経験(ACE)と制限された食品へのアクセスは、摂食障害(EDS)のリスクに関連しています。この研究では、米国の成人の全国的に代表的なサンプルにおける、特に制限された食品アクセスを含むACE、特に制限された食品アクセスを含むACEとの関係を調べました。 方法:参加者は、アルコールおよび関連条件に関する全国疫学調査の36,145人の回答者であり、子供の頃の食物の怠慢に関するデータを提供したIII(NESARC-III)でした。神経性食欲不振症(AN)、神経性過食症(BN)、および強打障害(BED)の有病率は、小児期の怠慢を拒否されたと報告した人のために決定されました。分析は、社会人口学的特性を調整した後の各ED診断の確率(モデル1)を比較し、子供の頃に他のACEと政府の財務支持をさらに調整しました(モデル2)。 結果:幼年期の食物怠慢の歴史を持つAN、BN、およびBEDの有病率の推定値は、それぞれ2.80%(SE = 0.81)、0.60%(SE = 0.21)、および3.50%(SE = 0.82)と0.80%(SE = 0.07)、0.30%(SE = 0.03)、および0.80%(SE = 0.05)が重要ではありません。完全に調整されたモデルでは、AN(AOR = 2.98 [95%CI = 1.56-5.71])およびBED(AOR = 2.95 [95%CI = 1.73-5.03])でED診断を受ける確率は有意に高かった。 結論:小児期の食物の怠慢を経験した人は、ANとベッドのリスクが高くなる可能性があり、リスクの上昇は、子供の頃の他の不利な経験や財政難に合わせて調整した後に存在します。

OBJECTIVE: Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and restricted food access have been associated with risk for eating disorders (EDs). This study examined the relationship between childhood food neglect, an ACE specifically involving restricted food access, and DSM-5-defined EDs in a nationally representative sample of U.S. adults, with a particular focus on whether the relationship persists after adjusting for other ACEs and family financial difficulties. METHODS: Participants were 36,145 respondents from the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III (NESARC-III) who provided data regarding childhood food neglect. Prevalence rates of lifetime anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN), and binge-eating disorder (BED) were determined for those who reported versus denied childhood food neglect. Analyses compared the odds of each ED diagnosis after adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics (Model 1) and further adjusting for other ACEs and governmental-financial support during childhood (Model 2). RESULTS: Prevalence estimates for AN, BN, and BED with a history of childhood food neglect were 2.80% (SE = 0.81), 0.60% (SE = 0.21), and 3.50% (SE = 0.82), respectively and 0.80% (SE = 0.07), 0.30% (SE = 0.03), and 0.80% (SE = 0.05) for those without a history (all significantly different, p < .05). In the fully-adjusted model, odds of having an ED diagnosis were significantly higher for AN (AOR = 2.98 [95% CI = 1.56-5.71]) and BED (AOR = 2.95 [95% CI = 1.73-5.03]) in respondents with a history of childhood food neglect compared with those without. CONCLUSION: Individuals who experience childhood food neglect may be at increased risk for AN and BED and the elevated risk exists after adjusting for other adverse experiences and financial difficulties during childhood.

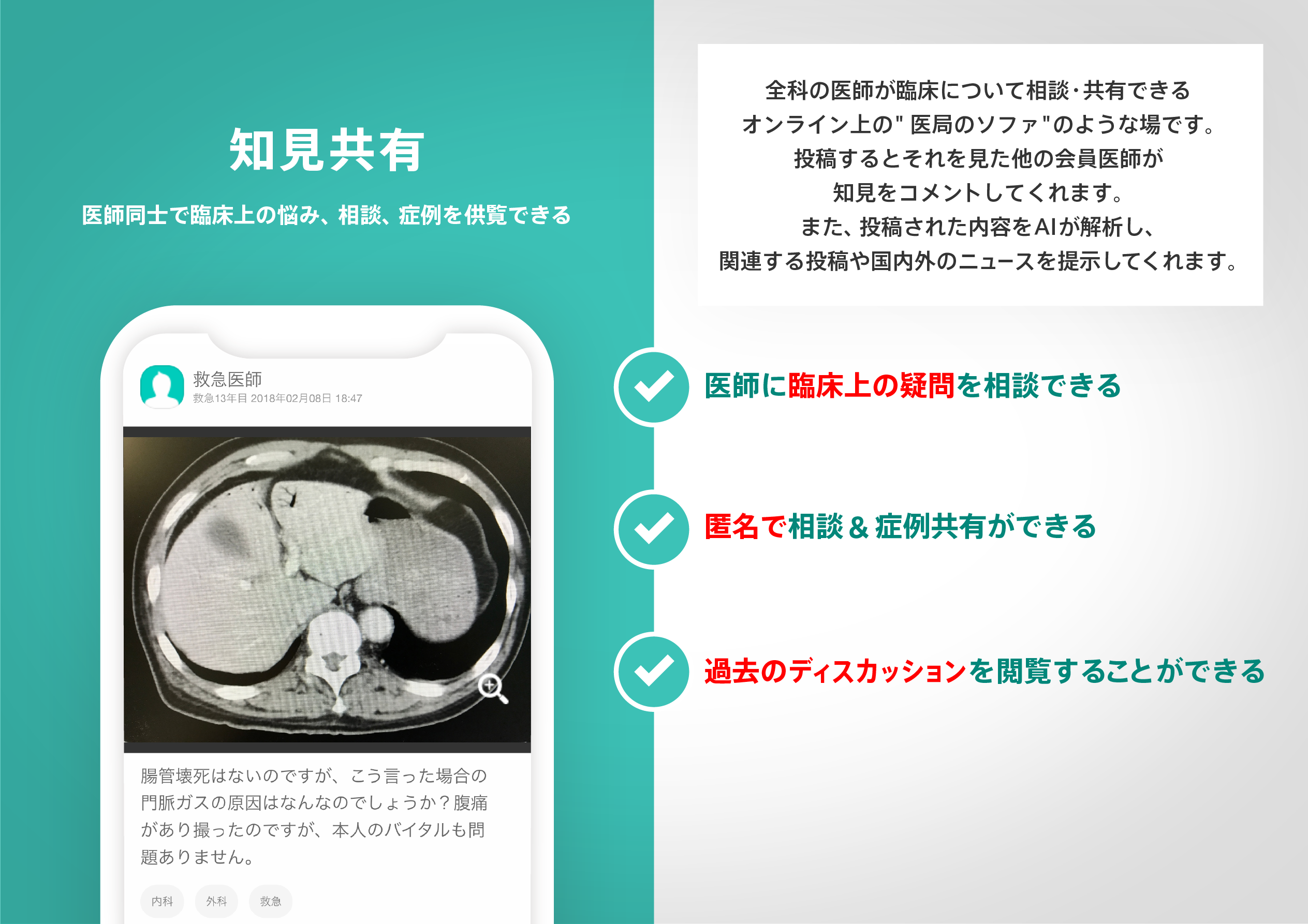

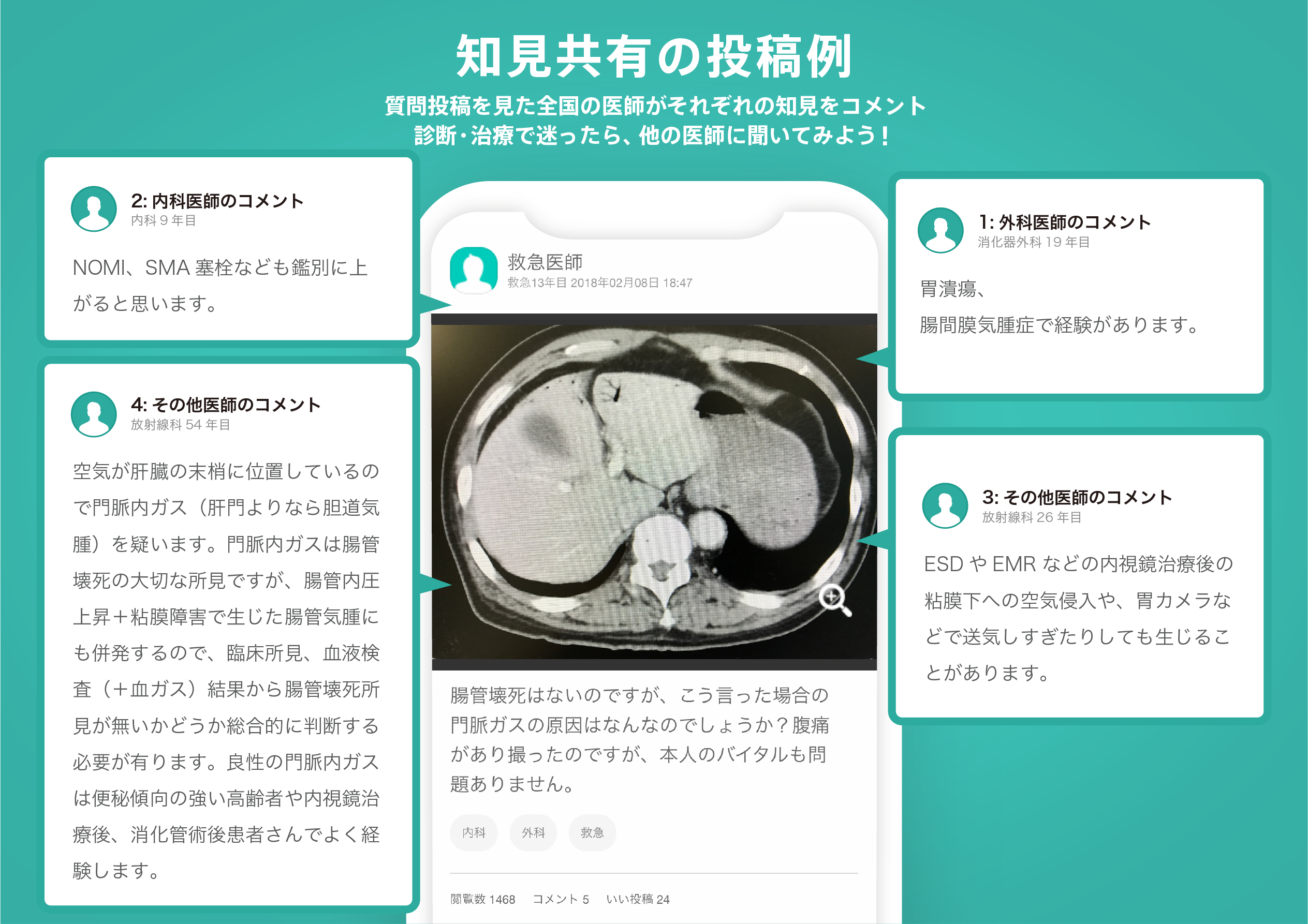

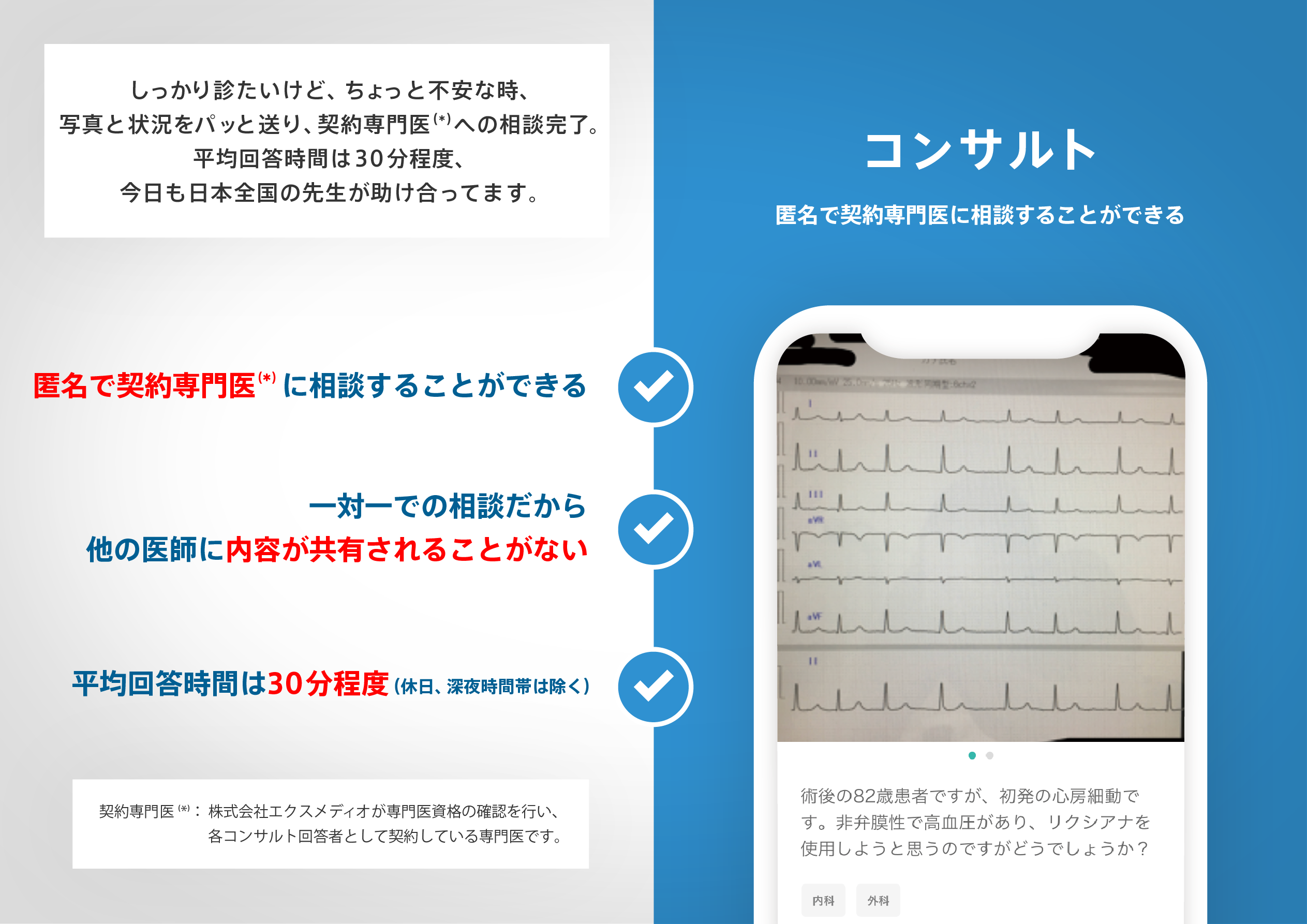

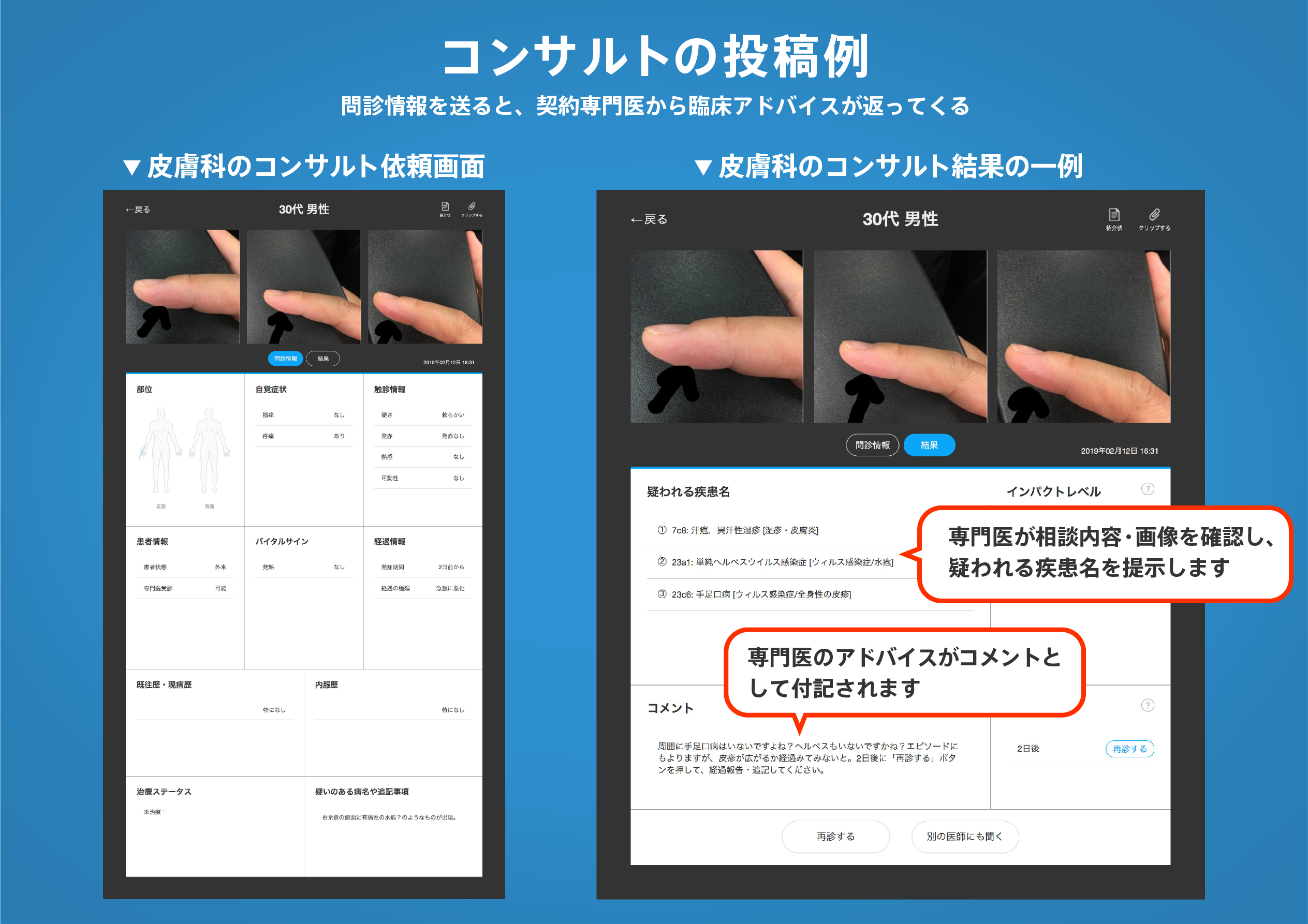

医師のための臨床サポートサービス

ヒポクラ x マイナビのご紹介

無料会員登録していただくと、さらに便利で効率的な検索が可能になります。