著名医師による解説が無料で読めます

すると翻訳の精度が向上します

背景: ホームレス人口は喫煙率が高く、禁煙に大きな障壁がある。タバコが原因となる疾患は、ホームレスの人々の罹患率および死亡率の主要原因の 1 つであり、この人口における喫煙の負担を軽減するための介入が緊急に必要であることが浮き彫りになっている。目的: ホームレス成人の禁煙介入へのアクセスを改善するように設計された介入によって、治療に従事または治療を受ける人数が増加するかどうか、およびホームレス成人の禁煙を支援するように設計された介入によって禁煙率が向上するかどうかを評価する。また、ホームレス成人に対する禁煙介入が薬物使用および精神的健康に影響を与えるかどうかも評価する。検索方法: Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group Specialized Register、MEDLINE、Embase、および PsycINFO で、住居なし*、ホームレス*、住宅の不安定さ、禁煙、タバコ使用障害、無煙タバコという用語を使用して研究を検索した。未発表の研究を特定するため、臨床試験登録簿も検索した。最新の検索日:2020年1月6日。選択基準:ホームレスで喫煙している人を募集し、以下の項目に重点を置いた介入を調査したランダム化比較試験を含めた。1) 関連するサポートサービスへのアクセスを改善する。2) 喫煙をやめる動機を高める。3) 行動支援、禁煙薬物療法、コンティンジェンシー管理、テキストまたはアプリベースの介入を含むがこれらに限定されない、人々が禁煙を達成できるように支援する。4) タバコを伴わない長期的なニコチン使用への移行を促す。適格な比較対象には、介入なし、通常のケア(研究で定義されている)、または別の形式の積極的介入が含まれていた。データ収集と分析:標準的なコクランの方法に従った。禁煙は、利用可能な最も厳格な定義を使用して、各研究の最長期の時点で、治療意図に基づいて測定された。可能な場合は、各研究について禁煙のリスク比(RR)と95%信頼区間(CI)を計算した。比較の種類(通常の禁煙ケアに加えて条件付き強化、より集中的な禁煙介入とより集中的でない禁煙介入、複数の問題に対する支援と禁煙支援のみ)ごとに適格な研究をグループ化し、必要に応じてMantel-Haenszelランダム効果モデルを用いてメタ分析を実施した。また、十分なデータが利用可能な場合は、禁煙の試み、精神および物質使用の重症度への影響に関するデータを抽出し、これらの結果をメタ分析した。主な結果:登録時に燃焼タバコを吸っていた1634人の参加者を含む10の研究を特定した。研究の1つは継続中だった。ほとんどの試験には、シェルターなどの地域ベースの場所から募集された参加者が含まれ、3つの試験には診療所から募集された参加者が含まれていた。3つの研究は、1つ以上の領域でバイアスのリスクが高いと判断した。不正確さの限界はあるが、確実性の低いエビデンスでは、条件付き強化(禁煙成功に対する報酬)と通常の禁煙ケアの併用は、通常のケア単独よりも禁煙促進に効果的ではなかった(RR 0.67、95% CI 0.16~2.77、試験 1 件、参加者 70 名)ことが判明した。バイアスのリスクと不正確さの限界はあるが、確実性の非常に低いエビデンスでは、6 か月後の追跡調査で、より集中的な行動的禁煙サポートが短期介入よりも禁煙促進に効果的であった(RR 1.64、95% CI 1.01~2.69、試験 3 件、参加者 657 名、I2 = 0 %)ことが判明した。バイアスと不正確さによって限定された確実性の低いエビデンスがあったが、マルチイシューサポート(他の課題や依存症への対処も含む禁煙サポート)は、禁煙を促進する上でターゲットを絞った禁煙サポートよりも優れていなかった(RR 0.95、95% CI 0.35~2.61、2件の試験、146人の参加者、I2 = 25%)。この種の介入に関するより多くのデータがあれば、これらのデータの解釈が変わる可能性がある。禁煙に対するテキストメッセージサポート、電子タバコ、または認知行動療法の効果を調べた単一の研究では、決定的な結果は得られなかった。精神的健康や物質使用の重症度などの副次的評価項目に関するデータは、臨床的に関連する違いがあったかどうかについて意味のある結論を導くには少なすぎた。禁煙ケアへのアクセスを増やすための介入を明示的に評価した研究は特定されなかったため、副次的評価項目である「治療を受けた参加者の数」を評価できなかった。著者の結論: ホームレスの人々に特に禁煙介入の効果を評価するには証拠が不十分です。より集中的な行動的禁煙介入は、それほど集中的ではない介入と比較して、適度な効果があることを示唆する証拠はいくつかありましたが、この証拠の確実性は非常に低く、さらなる研究によってこの効果が強まることも弱まることもあります。禁煙支援の提供とそれが禁煙の試みに及ぼす影響が、ホームレスの人々の精神的健康やその他の物質使用の結果に何らかの影響を与えるかどうかを評価するには証拠が不十分です。標準的な禁煙治療がホームレスの人々に一般の人々と異なる効果をもたらすと考える理由は何もありませんが、これらの結果は、ホームレスの人々が直面する日常的な課題という文脈で、ホームレスの人々を関与させ支援するための追加の方法を扱う質の高い研究の必要性を浮き彫りにしています。これらの研究は十分な検出力を持ち、参加者を少なくとも 6 か月間の長期追跡調査に参加させるよう努力すべきです。研究では、禁煙サービスへのアクセスを増やす介入策も検討し、ホームレスの人々の間での喫煙の社会的および環境的影響に対処する必要があります。最後に、研究では、喫煙の中止が精神衛生と薬物使用の結果に与える影響を調査する必要があります。

背景: ホームレス人口は喫煙率が高く、禁煙に大きな障壁がある。タバコが原因となる疾患は、ホームレスの人々の罹患率および死亡率の主要原因の 1 つであり、この人口における喫煙の負担を軽減するための介入が緊急に必要であることが浮き彫りになっている。目的: ホームレス成人の禁煙介入へのアクセスを改善するように設計された介入によって、治療に従事または治療を受ける人数が増加するかどうか、およびホームレス成人の禁煙を支援するように設計された介入によって禁煙率が向上するかどうかを評価する。また、ホームレス成人に対する禁煙介入が薬物使用および精神的健康に影響を与えるかどうかも評価する。検索方法: Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group Specialized Register、MEDLINE、Embase、および PsycINFO で、住居なし*、ホームレス*、住宅の不安定さ、禁煙、タバコ使用障害、無煙タバコという用語を使用して研究を検索した。未発表の研究を特定するため、臨床試験登録簿も検索した。最新の検索日:2020年1月6日。選択基準:ホームレスで喫煙している人を募集し、以下の項目に重点を置いた介入を調査したランダム化比較試験を含めた。1) 関連するサポートサービスへのアクセスを改善する。2) 喫煙をやめる動機を高める。3) 行動支援、禁煙薬物療法、コンティンジェンシー管理、テキストまたはアプリベースの介入を含むがこれらに限定されない、人々が禁煙を達成できるように支援する。4) タバコを伴わない長期的なニコチン使用への移行を促す。適格な比較対象には、介入なし、通常のケア(研究で定義されている)、または別の形式の積極的介入が含まれていた。データ収集と分析:標準的なコクランの方法に従った。禁煙は、利用可能な最も厳格な定義を使用して、各研究の最長期の時点で、治療意図に基づいて測定された。可能な場合は、各研究について禁煙のリスク比(RR)と95%信頼区間(CI)を計算した。比較の種類(通常の禁煙ケアに加えて条件付き強化、より集中的な禁煙介入とより集中的でない禁煙介入、複数の問題に対する支援と禁煙支援のみ)ごとに適格な研究をグループ化し、必要に応じてMantel-Haenszelランダム効果モデルを用いてメタ分析を実施した。また、十分なデータが利用可能な場合は、禁煙の試み、精神および物質使用の重症度への影響に関するデータを抽出し、これらの結果をメタ分析した。主な結果:登録時に燃焼タバコを吸っていた1634人の参加者を含む10の研究を特定した。研究の1つは継続中だった。ほとんどの試験には、シェルターなどの地域ベースの場所から募集された参加者が含まれ、3つの試験には診療所から募集された参加者が含まれていた。3つの研究は、1つ以上の領域でバイアスのリスクが高いと判断した。不正確さの限界はあるが、確実性の低いエビデンスでは、条件付き強化(禁煙成功に対する報酬)と通常の禁煙ケアの併用は、通常のケア単独よりも禁煙促進に効果的ではなかった(RR 0.67、95% CI 0.16~2.77、試験 1 件、参加者 70 名)ことが判明した。バイアスのリスクと不正確さの限界はあるが、確実性の非常に低いエビデンスでは、6 か月後の追跡調査で、より集中的な行動的禁煙サポートが短期介入よりも禁煙促進に効果的であった(RR 1.64、95% CI 1.01~2.69、試験 3 件、参加者 657 名、I2 = 0 %)ことが判明した。バイアスと不正確さによって限定された確実性の低いエビデンスがあったが、マルチイシューサポート(他の課題や依存症への対処も含む禁煙サポート)は、禁煙を促進する上でターゲットを絞った禁煙サポートよりも優れていなかった(RR 0.95、95% CI 0.35~2.61、2件の試験、146人の参加者、I2 = 25%)。この種の介入に関するより多くのデータがあれば、これらのデータの解釈が変わる可能性がある。禁煙に対するテキストメッセージサポート、電子タバコ、または認知行動療法の効果を調べた単一の研究では、決定的な結果は得られなかった。精神的健康や物質使用の重症度などの副次的評価項目に関するデータは、臨床的に関連する違いがあったかどうかについて意味のある結論を導くには少なすぎた。禁煙ケアへのアクセスを増やすための介入を明示的に評価した研究は特定されなかったため、副次的評価項目である「治療を受けた参加者の数」を評価できなかった。著者の結論: ホームレスの人々に特に禁煙介入の効果を評価するには証拠が不十分です。より集中的な行動的禁煙介入は、それほど集中的ではない介入と比較して、適度な効果があることを示唆する証拠はいくつかありましたが、この証拠の確実性は非常に低く、さらなる研究によってこの効果が強まることも弱まることもあります。禁煙支援の提供とそれが禁煙の試みに及ぼす影響が、ホームレスの人々の精神的健康やその他の物質使用の結果に何らかの影響を与えるかどうかを評価するには証拠が不十分です。標準的な禁煙治療がホームレスの人々に一般の人々と異なる効果をもたらすと考える理由は何もありませんが、これらの結果は、ホームレスの人々が直面する日常的な課題という文脈で、ホームレスの人々を関与させ支援するための追加の方法を扱う質の高い研究の必要性を浮き彫りにしています。これらの研究は十分な検出力を持ち、参加者を少なくとも 6 か月間の長期追跡調査に参加させるよう努力すべきです。研究では、禁煙サービスへのアクセスを増やす介入策も検討し、ホームレスの人々の間での喫煙の社会的および環境的影響に対処する必要があります。最後に、研究では、喫煙の中止が精神衛生と薬物使用の結果に与える影響を調査する必要があります。

BACKGROUND: Populations experiencing homelessness have high rates of tobacco use and experience substantial barriers to cessation. Tobacco-caused conditions are among the leading causes of morbidity and mortality among people experiencing homelessness, highlighting an urgent need for interventions to reduce the burden of tobacco use in this population. OBJECTIVES: To assess whether interventions designed to improve access to tobacco cessation interventions for adults experiencing homelessness lead to increased numbers engaging in or receiving treatment, and whether interventions designed to help adults experiencing homelessness to quit tobacco lead to increased tobacco abstinence. To also assess whether tobacco cessation interventions for adults experiencing homelessness affect substance use and mental health. SEARCH METHODS: We searched the Cochrane Tobacco Addiction Group Specialized Register, MEDLINE, Embase and PsycINFO for studies using the terms: un-housed*, homeless*, housing instability, smoking cessation, tobacco use disorder, smokeless tobacco. We also searched trial registries to identify unpublished studies. Date of the most recent search: 06 January 2020. SELECTION CRITERIA: We included randomized controlled trials that recruited people experiencing homelessness who used tobacco, and investigated interventions focused on the following: 1) improving access to relevant support services; 2) increasing motivation to quit tobacco use; 3) helping people to achieve abstinence, including but not limited to behavioral support, tobacco cessation pharmacotherapies, contingency management, and text- or app-based interventions; or 4) encouraging transitions to long-term nicotine use that did not involve tobacco. Eligible comparators included no intervention, usual care (as defined by the studies), or another form of active intervention. DATA COLLECTION AND ANALYSIS: We followed standard Cochrane methods. Tobacco cessation was measured at the longest time point for each study, on an intention-to-treat basis, using the most rigorous definition available. We calculated risk ratios (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for smoking cessation for each study where possible. We grouped eligible studies according to the type of comparison (contingent reinforcement in addition to usual smoking cessation care; more versus less intensive smoking cessation interventions; and multi-issue support versus smoking cessation support only), and carried out meta-analyses where appropriate, using a Mantel-Haenszel random-effects model. We also extracted data on quit attempts, effects on mental and substance-use severity, and meta-analyzed these outcomes where sufficient data were available. MAIN RESULTS: We identified 10 studies involving 1634 participants who smoked combustible tobacco at enrolment. One of the studies was ongoing. Most of the trials included participants who were recruited from community-based sites such as shelters, and three included participants who were recruited from clinics. We judged three studies to be at high risk of bias in one or more domains. We identified low-certainty evidence, limited by imprecision, that contingent reinforcement (rewards for successful smoking cessation) plus usual smoking cessation care was not more effective than usual care alone in promoting abstinence (RR 0.67, 95% CI 0.16 to 2.77; 1 trial, 70 participants). We identified very low-certainty evidence, limited by risk of bias and imprecision, that more intensive behavioral smoking cessation support was more effective than brief intervention in promoting abstinence at six-month follow-up (RR 1.64, 95% CI 1.01 to 2.69; 3 trials, 657 participants; I2 = 0%). There was low-certainty evidence, limited by bias and imprecision, that multi-issue support (cessation support that also encompassed help to deal with other challenges or addictions) was not superior to targeted smoking cessation support in promoting abstinence (RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.35 to 2.61; 2 trials, 146 participants; I2 = 25%). More data on these types of interventions are likely to change our interpretation of these data. Single studies that examined the effects of text-messaging support, e-cigarettes, or cognitive behavioral therapy for smoking cessation provided inconclusive results. Data on secondary outcomes, including mental health and substance use severity, were too sparse to draw any meaningful conclusions on whether there were clinically-relevant differences. We did not identify any studies that explicitly assessed interventions to increase access to tobacco cessation care; we were therefore unable to assess our secondary outcome 'number of participants receiving treatment'. AUTHORS' CONCLUSIONS: There is insufficient evidence to assess the effects of any tobacco cessation interventions specifically in people experiencing homelessness. Although there was some evidence to suggest a modest benefit of more intensive behavioral smoking cessation interventions when compared to less intensive interventions, our certainty in this evidence was very low, meaning that further research could either strengthen or weaken this effect. There is insufficient evidence to assess whether the provision of tobacco cessation support and its effects on quit attempts has any effect on the mental health or other substance-use outcomes of people experiencing homelessness. Although there is no reason to believe that standard tobacco cessation treatments work any differently in people experiencing homelessness than in the general population, these findings highlight a need for high-quality studies that address additional ways to engage and support people experiencing homelessness, in the context of the daily challenges they face. These studies should have adequate power and put effort into retaining participants for long-term follow-up of at least six months. Studies should also explore interventions that increase access to cessation services, and address the social and environmental influences of tobacco use among people experiencing homelessness. Finally, studies should explore the impact of tobacco cessation on mental health and substance-use outcomes.

医師のための臨床サポートサービス

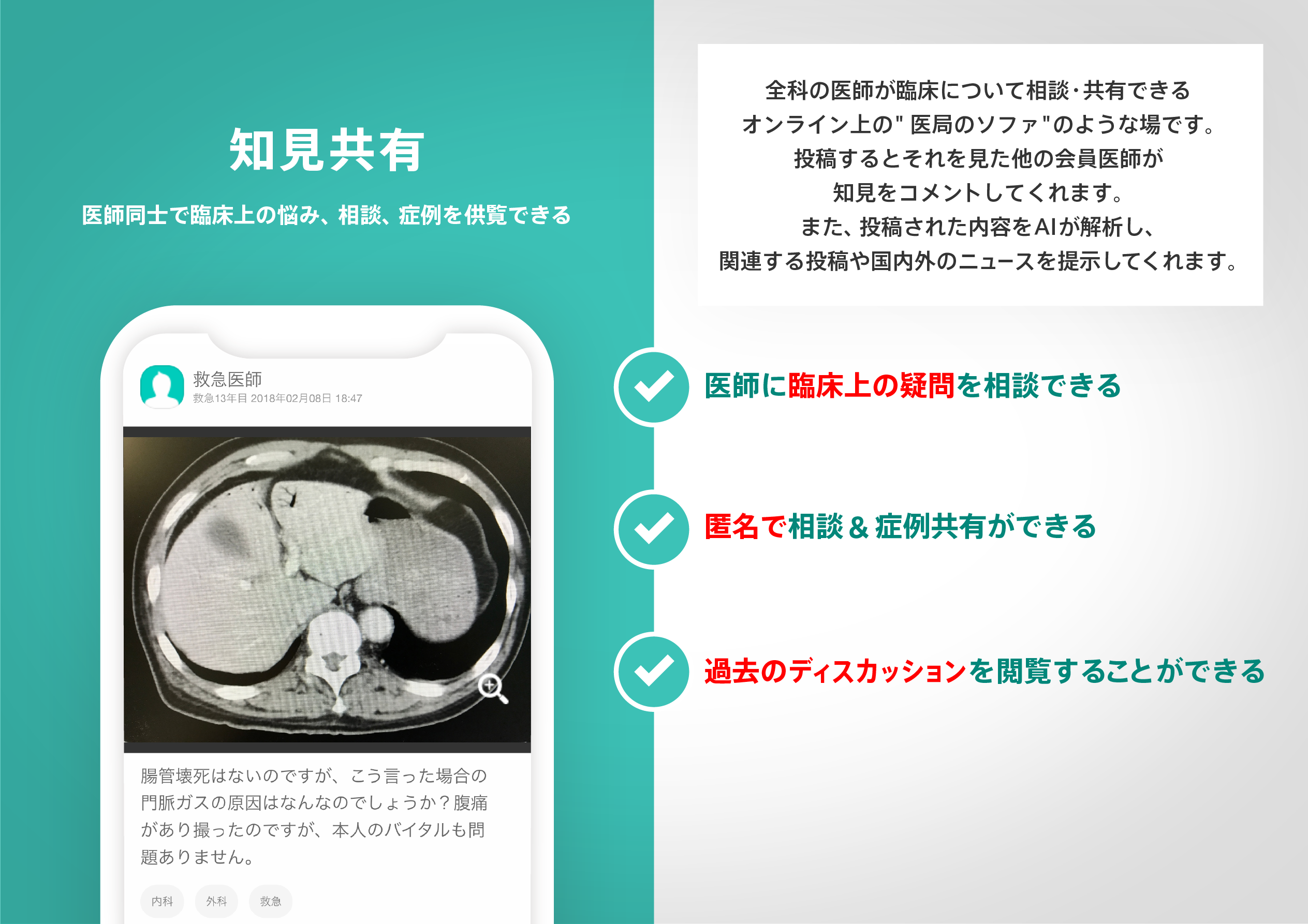

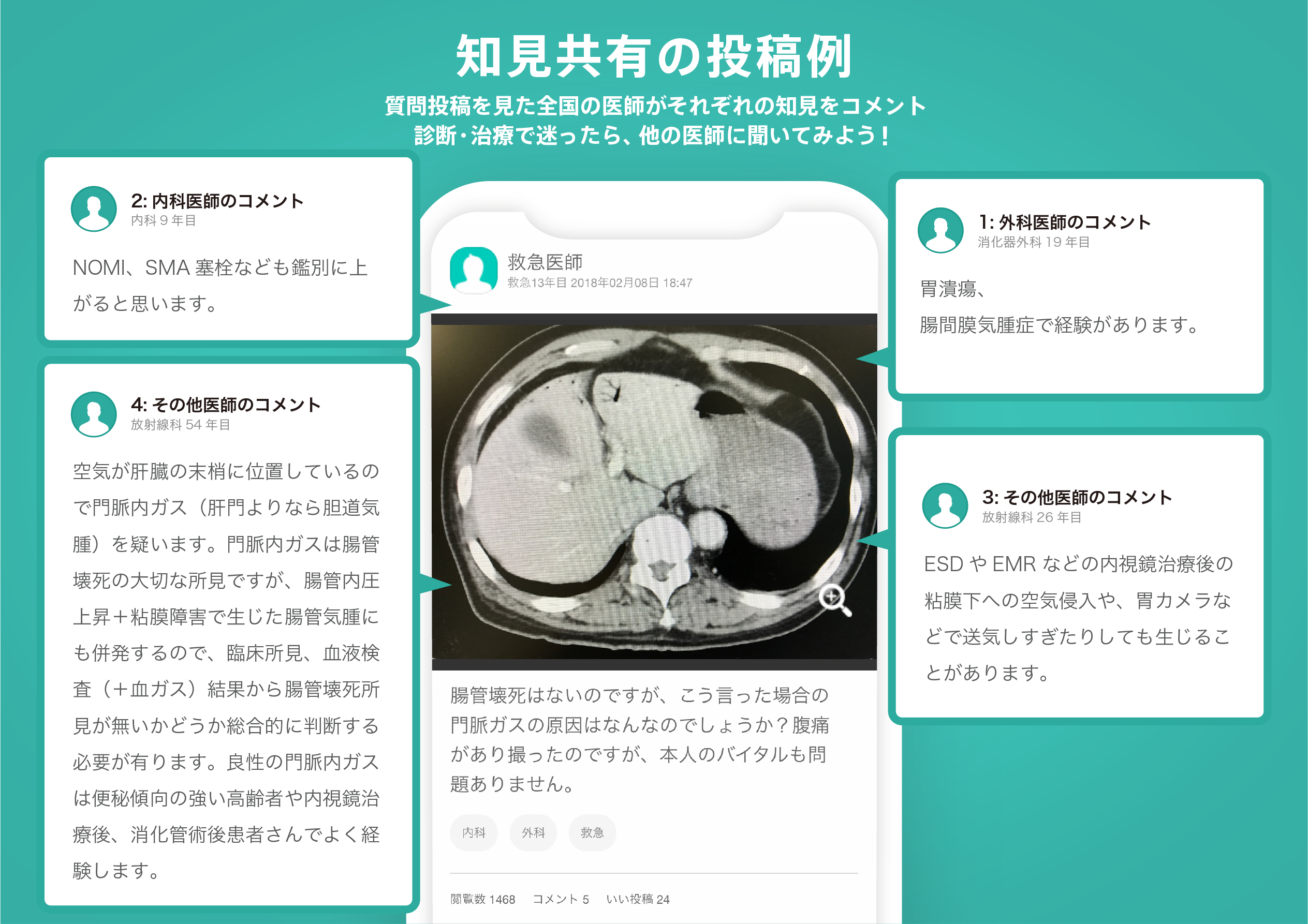

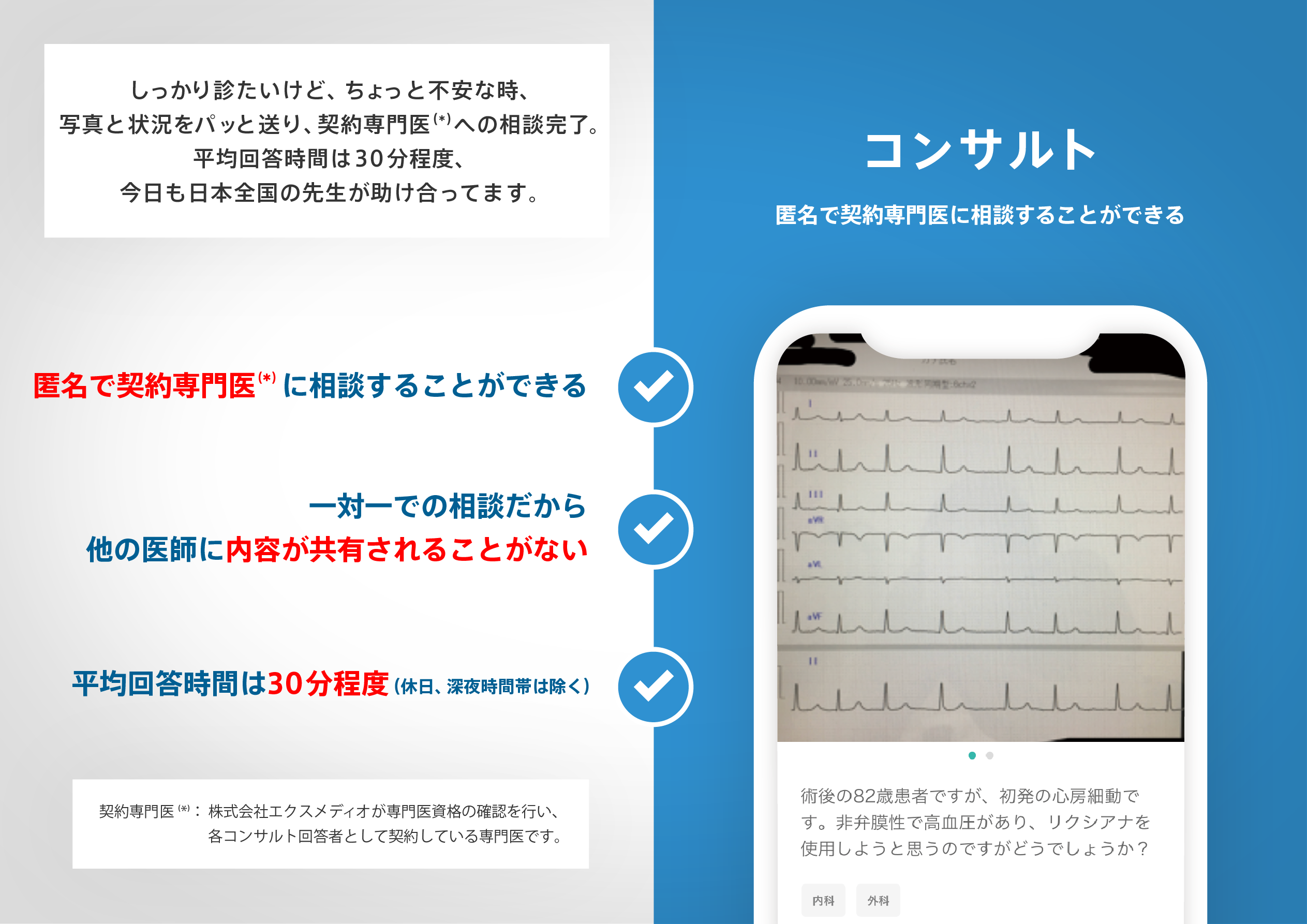

ヒポクラ x マイナビのご紹介

無料会員登録していただくと、さらに便利で効率的な検索が可能になります。