著名医師による解説が無料で読めます

すると翻訳の精度が向上します

「何もする必要はない」(Beckett 2012: 11)。サミュエル・ベケットの戯曲『ゴドーを待ちながら』は医療に関するものではないが、その最初の一文は予後と診断の間をさまよっているように見え、処方箋が処方されないことが明らかであるにもかかわらず、ある種の実存的な「医療」が進行中であることを示唆している。この劇の二人の中心人物、ウラジーミルとエストラゴンにとって、「なすべきことは何もない」という言葉は、ウラジーミル・レーニンの有名な質問「何をなすべきか?」からの治療的政治行動の緊急性を空にするものである。劇の地平線上に起こるあらゆる変化の可能性は、「我々はゴドーを待っている」という固定リフレインの惰性によって狂わされる。待つということは、有名なことに二度起こった無であり(Mercier 1956: 6)、ベケットの初期の多くの批判的な受け取り方において、実存的な人間の状態の表現としてみなされるようになった(Graver and Federman 1979)。この劇が初めて上演された 1950 年代初期には、おそらく、戦後のヨーロッパがまだ居住可能な未来が剥奪された現在にあるという可能性よりも、抽象概念のほうが重要な吸収に利用可能であった (Kenner 1973: 133; Gibson 2010: 108) – 終わりのない不特定の災害の後、変化の本当の希望を持たずに生き続ける時代。ベケットの戯曲は、現在を変えるために何が起こるかという約束を通して、忍耐の一形態となる待ちを具体化している。なぜなら、そのような実践には常に未来への何らかの方向性があるからである。しかし、Godot が明らかに利用できないことは、最も明白な前置詞または関係である for (Schweizer 2008: 11) を待つという行為から切り離します。立ち止まるほど弱くも、立ち去るほど強くもないウラジミールとエストラゴンは、耐え続け、最後にはゴドーを待つのではなく、お互いに、時にはお互いを待ち続ける。この章では、人間の経験における待つことの場所についての実存的な主張に細心の注意を払うが、待つことは特定の歴史的瞬間や生活世界の約束や物語、そしてそれらの独特の時間の理解方法によって大きく形作られることを示唆する。実際、ゴドーの待合室に滞留することが人間の実存的な状況を物語っているように見えるとしたら、それは未来の約束がますます手に入らないと感じられる時代に、この劇が見つけ、そして見つけ続けている観客が固執しているからであると私たちは主張するでしょう。ゴドーの登場人物たちは観客とともに診断を待ちますが、それは彼らの予後でもあります:「何もする必要はありません」。おそらく、ゴドーのゆっくりとしたモダニズムがこれほど鮮明に発見され、その痕跡を残した理由の 1 つは、モダニティの支配的な時間風景の否定されている裏側に注意を向けることに固執したからでしょう。 1931 年、オルダス・ハクスリーは、「速度は、真に現代的な喜びを提供する」と述べることができました (Huxley 2001: 263)。美的モダニズムを、社会的衝撃の反映として読むことは、極めて一般的なこととなってきました。新しい、そしてペースの速いレーシングプレゼント。飛行機、電車、自動車。ラグタイムとジャズ。ひらめきと革命。電信と電話。生産ラインと新しいマスメディア: 人文科学の学問は、20 世紀初頭から半ばの近代が、良くも悪くも、どのようにして生活の加速を生み出し、スピード感を記録し増大させることができる技術を形作ったのかを徹底的に掘り下げてきました (Duffy 2009)。ポール・ヴィリリオ(2006)は、より現代的な瞬間に取り組み、美的実践にはあまり関心を持たず、時間を圧縮し、短縮し、分断した加速の論理が、依然として現代性とその破壊への衝動の中心にどのように座っているかを説明しました。一方、ジョナサン・クレイリー (2013) は、不眠テクノロジーによって促進された 24 時間 365 日の利用可能性の文化を批判し、休息を遅らせることさえも体現された抵抗行為に変えてしまった。しかし、エリザベス・キルツォグルーとボブ・シンプソンの「クロノクラシー」の考えが示唆しているように(本書)、現代に折り畳まれた別の時代が常に存在した。例えば、新興工業化されたヨーロッパにおける労働者階級の管理され機械化された時間は、彼らの利益に基づいて形成されていない進歩的な未来のバージョンを提供するために一貫して使用されてきました(Thompson 1967)。クレイグ・ジェフリーはまた、「慢性的で無駄な待機」(Jeffery 2010: 3) を、帝国と近代化の加速のための物質的資源の多くを提供した植民地化された人々の特定の一時的な経験であると特定し、それが帝国の経験の顕著な特徴であると指摘した。 1960 年代以降、世界中でサバルタン民族が活動しています。ベンディクセンとエリクセンは確かに、特定のグループにとって待つことは権力と支配の表現となり、脆弱性と屈辱を生み出す可能性があると指摘している(2018: 92)。そして、現代のグローバル・ノースの後期リベラリズムにおいて、「新たな慢性的な」時間的想像がより一般的に明白になっている一方で(Cazdyn 2012)、「慢性的で無駄な待機」の最も深刻な経験の多くは、依然として特定の性別、人種に「ゾーン化」されている。 、およびクラス分けされた方法。リサ・バライツァーが『Enduring Time』(2017)で主張したように、加速感は増し続けているにもかかわらず、可能性のある未来に向けて巻き取られていく時間は、中断、停止、遅延、遅さの経験である現代の瞬間に解き明かされているように見えるため、非常に異なる方法で感情的な生活を強く主張します。しかし、ここでは、20世紀の初期の瞬間に遡るのではなく、この持続する時間の感覚を追跡し、人が足を踏み入れるかもしれない未来から切り離されて待つことが、感情の重要な特徴として理解されるようになった方法に注目します。この状態は「メランコリア」、またはより現代的な表現では「うつ病」と呼ばれます。これは、どちらかの状態が単に現代への反応である、あるいはさらに強く言えば社会構造であると主張するわけではありません。また、不平等や不正義といった他の社会関係の結果として生じる苦痛を医療化しようとするものでもありません(Thomas et al. 2018)。むしろ、私たちは、20世紀ヨーロッパにおけるメランコリーの理解が、時間的風景や心理的想像の輪郭を形成し、形成し続ける、行き詰まり、中断され、妨げられ、または把握できない時間に関する特定のアイデアや感覚を通じてどのように焦点化されるようになったのかを探ることに興味があります。 (後期)近代の。さらに、私たちは、うつ病の文脈におけるケアは、心理社会的な関係や経験と密接に関係しており、したがって体質的に「生物医学以上の」または心理学的なものであると理解していますが(Hinchliffe et al. 2018)、最終的にはその提案とその内容に左右される可能性があると主張します。長期間の使用と、もはや流れない一時的な経験を持つ人々と一緒に滞在する能力。ここでの専門的な視点は人類学的なものではありませんが、待つことの経験と実践を通じてメランコリーとうつ病を考察するという私たちの関心は、私たちの章を重要な人類学文献と接触させることになります。ガッセン・ハーゲは学際的な著書の中で、待つことを常に実存的であり、歴史的に明確化または状況的に表現される経験であると説明しています (Hage 2009: 4, 6)。 Manpreet Janeja と Andreas Bandak も同様に、焦点を当てた民族誌的研究が待ちの詩学とその政治の両方をどのように解明できるかを実証しながら、待ちの分析には実存的な観点とより明確な社会的または制度的な観点の間を行き来する能力が必要であることを示唆しています(Janeja and Bandak 2018: 3)。しかし、この章は、より分散した、折衷的な、そしてテキストの経験のアーカイブを使用して、実存的、文化的、社会歴史的経験とヨーロッパ(後期)近代の理論に根本的に絡み合った状態としてのメランコリー/うつ病の理論的説明を開きます。しかし、待つことに対するこうした人類学的アプローチの風潮の中に広く留まりながら、19世紀後半から20世紀初頭にかけての現象学的精神医学の注目すべき伝統が、明らかに現れた精神的苦痛の生きた経験の説明間の関係を追跡する重要な機会を提供していると我々は提案する。実存哲学や、より広範な社会歴史的時間の説明と並行して。 20世紀初頭のヨーロッパと北アメリカで、時間が科学、芸術、人文科学にわたる激しい議論のテーマとなるにつれ、複数の分野が直感的/主観的時間の説明と数学的/客観的時間の理解の間の緊張を探求した(Fryxell 2019: 5–6) )。現象学的精神医学は、エミール・クレペリン (Broome et al. 2012: 90) によって例示された精神病理への支配的な三人称アプローチを拒否し、一人称、つまり精神状態の混乱に関する主観的な経験に細心の注意を払うことを支持し、この文脈において独特のアプローチを確立した。であること。この学問は、20世紀の最初の30年間に、アンリ・ベルクソンとマルティン・ハイデッガーの時間性に関する新しい哲学に深く影響を受けており、その重要な洞察の1つは、慢性的な精神的苦痛は、生きている時間の感覚の障害として理解できるということでした。しかし、現象学的精神医学は、治療の時間的要求(Fryxell 2019: 23)、つまり臨床的遭遇の相互主観性に縛られた時間、または単に治療にかかる時間には、ほとんど明確な注意を払っていませんでした。しかし、歴史的に現象学的精神医学と並んで登場した精神分析は、複雑で、しばしば果てしなく続くように見える治療の時間性を、特別な自意識とともに反映することを主張した(Freud 1937)。現象学的精神医学と精神分析はどちらも、近代の状況と、工業化された戦争の壊滅的な経験との明確な対話の中で発展しましたが、現象学が精神疾患の経験において後退する正常性の時間的態度を否定的に明確に表現するのに対し、精神分析は精神病理学のリズムと必然性を利用しました。すべての精神生活の構造と、単純に直線的、目的論的、スムーズに流れることのできない時間の精神的生活を照らす方法として、病気になるということ。精神分析は、何もせずに待つ感覚が生きている時間にふさわしいものを壊すということを示唆するのではなく、そのような経験は精神的な生活の避けられない条件の一部であると理解するようになりました。したがって、精神分析は、精神的苦痛の慢性状態を封じ込め、理解し、改善するために、特に慢性的な治療法、つまり時間とケア、そして思い出し、繰り返し、取り組み続けることの提供(Freud 2014)を提供します。この論文は、心の慢性化と忍耐が影響するより広範な心理社会的文脈との間の関連性を強調することによって、「待つのではなく、我慢する」という精神分析の時間的実践の価値について、歴史的に微妙な意味を明らかにすることを目的としている。また、うつ病、一時性、歴史的および心理社会的経験の関係に特に注目することで、英国の国民保健サービスが提供する現代の精神医療における時間の使い方に関する緊急の議論が暫定的に再構築される可能性があることも示唆します。

「何もする必要はない」(Beckett 2012: 11)。サミュエル・ベケットの戯曲『ゴドーを待ちながら』は医療に関するものではないが、その最初の一文は予後と診断の間をさまよっているように見え、処方箋が処方されないことが明らかであるにもかかわらず、ある種の実存的な「医療」が進行中であることを示唆している。この劇の二人の中心人物、ウラジーミルとエストラゴンにとって、「なすべきことは何もない」という言葉は、ウラジーミル・レーニンの有名な質問「何をなすべきか?」からの治療的政治行動の緊急性を空にするものである。劇の地平線上に起こるあらゆる変化の可能性は、「我々はゴドーを待っている」という固定リフレインの惰性によって狂わされる。待つということは、有名なことに二度起こった無であり(Mercier 1956: 6)、ベケットの初期の多くの批判的な受け取り方において、実存的な人間の状態の表現としてみなされるようになった(Graver and Federman 1979)。この劇が初めて上演された 1950 年代初期には、おそらく、戦後のヨーロッパがまだ居住可能な未来が剥奪された現在にあるという可能性よりも、抽象概念のほうが重要な吸収に利用可能であった (Kenner 1973: 133; Gibson 2010: 108) – 終わりのない不特定の災害の後、変化の本当の希望を持たずに生き続ける時代。ベケットの戯曲は、現在を変えるために何が起こるかという約束を通して、忍耐の一形態となる待ちを具体化している。なぜなら、そのような実践には常に未来への何らかの方向性があるからである。しかし、Godot が明らかに利用できないことは、最も明白な前置詞または関係である for (Schweizer 2008: 11) を待つという行為から切り離します。立ち止まるほど弱くも、立ち去るほど強くもないウラジミールとエストラゴンは、耐え続け、最後にはゴドーを待つのではなく、お互いに、時にはお互いを待ち続ける。この章では、人間の経験における待つことの場所についての実存的な主張に細心の注意を払うが、待つことは特定の歴史的瞬間や生活世界の約束や物語、そしてそれらの独特の時間の理解方法によって大きく形作られることを示唆する。実際、ゴドーの待合室に滞留することが人間の実存的な状況を物語っているように見えるとしたら、それは未来の約束がますます手に入らないと感じられる時代に、この劇が見つけ、そして見つけ続けている観客が固執しているからであると私たちは主張するでしょう。ゴドーの登場人物たちは観客とともに診断を待ちますが、それは彼らの予後でもあります:「何もする必要はありません」。おそらく、ゴドーのゆっくりとしたモダニズムがこれほど鮮明に発見され、その痕跡を残した理由の 1 つは、モダニティの支配的な時間風景の否定されている裏側に注意を向けることに固執したからでしょう。 1931 年、オルダス・ハクスリーは、「速度は、真に現代的な喜びを提供する」と述べることができました (Huxley 2001: 263)。美的モダニズムを、社会的衝撃の反映として読むことは、極めて一般的なこととなってきました。新しい、そしてペースの速いレーシングプレゼント。飛行機、電車、自動車。ラグタイムとジャズ。ひらめきと革命。電信と電話。生産ラインと新しいマスメディア: 人文科学の学問は、20 世紀初頭から半ばの近代が、良くも悪くも、どのようにして生活の加速を生み出し、スピード感を記録し増大させることができる技術を形作ったのかを徹底的に掘り下げてきました (Duffy 2009)。ポール・ヴィリリオ(2006)は、より現代的な瞬間に取り組み、美的実践にはあまり関心を持たず、時間を圧縮し、短縮し、分断した加速の論理が、依然として現代性とその破壊への衝動の中心にどのように座っているかを説明しました。一方、ジョナサン・クレイリー (2013) は、不眠テクノロジーによって促進された 24 時間 365 日の利用可能性の文化を批判し、休息を遅らせることさえも体現された抵抗行為に変えてしまった。しかし、エリザベス・キルツォグルーとボブ・シンプソンの「クロノクラシー」の考えが示唆しているように(本書)、現代に折り畳まれた別の時代が常に存在した。例えば、新興工業化されたヨーロッパにおける労働者階級の管理され機械化された時間は、彼らの利益に基づいて形成されていない進歩的な未来のバージョンを提供するために一貫して使用されてきました(Thompson 1967)。クレイグ・ジェフリーはまた、「慢性的で無駄な待機」(Jeffery 2010: 3) を、帝国と近代化の加速のための物質的資源の多くを提供した植民地化された人々の特定の一時的な経験であると特定し、それが帝国の経験の顕著な特徴であると指摘した。 1960 年代以降、世界中でサバルタン民族が活動しています。ベンディクセンとエリクセンは確かに、特定のグループにとって待つことは権力と支配の表現となり、脆弱性と屈辱を生み出す可能性があると指摘している(2018: 92)。そして、現代のグローバル・ノースの後期リベラリズムにおいて、「新たな慢性的な」時間的想像がより一般的に明白になっている一方で(Cazdyn 2012)、「慢性的で無駄な待機」の最も深刻な経験の多くは、依然として特定の性別、人種に「ゾーン化」されている。 、およびクラス分けされた方法。リサ・バライツァーが『Enduring Time』(2017)で主張したように、加速感は増し続けているにもかかわらず、可能性のある未来に向けて巻き取られていく時間は、中断、停止、遅延、遅さの経験である現代の瞬間に解き明かされているように見えるため、非常に異なる方法で感情的な生活を強く主張します。しかし、ここでは、20世紀の初期の瞬間に遡るのではなく、この持続する時間の感覚を追跡し、人が足を踏み入れるかもしれない未来から切り離されて待つことが、感情の重要な特徴として理解されるようになった方法に注目します。この状態は「メランコリア」、またはより現代的な表現では「うつ病」と呼ばれます。これは、どちらかの状態が単に現代への反応である、あるいはさらに強く言えば社会構造であると主張するわけではありません。また、不平等や不正義といった他の社会関係の結果として生じる苦痛を医療化しようとするものでもありません(Thomas et al. 2018)。むしろ、私たちは、20世紀ヨーロッパにおけるメランコリーの理解が、時間的風景や心理的想像の輪郭を形成し、形成し続ける、行き詰まり、中断され、妨げられ、または把握できない時間に関する特定のアイデアや感覚を通じてどのように焦点化されるようになったのかを探ることに興味があります。 (後期)近代の。さらに、私たちは、うつ病の文脈におけるケアは、心理社会的な関係や経験と密接に関係しており、したがって体質的に「生物医学以上の」または心理学的なものであると理解していますが(Hinchliffe et al. 2018)、最終的にはその提案とその内容に左右される可能性があると主張します。長期間の使用と、もはや流れない一時的な経験を持つ人々と一緒に滞在する能力。ここでの専門的な視点は人類学的なものではありませんが、待つことの経験と実践を通じてメランコリーとうつ病を考察するという私たちの関心は、私たちの章を重要な人類学文献と接触させることになります。ガッセン・ハーゲは学際的な著書の中で、待つことを常に実存的であり、歴史的に明確化または状況的に表現される経験であると説明しています (Hage 2009: 4, 6)。 Manpreet Janeja と Andreas Bandak も同様に、焦点を当てた民族誌的研究が待ちの詩学とその政治の両方をどのように解明できるかを実証しながら、待ちの分析には実存的な観点とより明確な社会的または制度的な観点の間を行き来する能力が必要であることを示唆しています(Janeja and Bandak 2018: 3)。しかし、この章は、より分散した、折衷的な、そしてテキストの経験のアーカイブを使用して、実存的、文化的、社会歴史的経験とヨーロッパ(後期)近代の理論に根本的に絡み合った状態としてのメランコリー/うつ病の理論的説明を開きます。しかし、待つことに対するこうした人類学的アプローチの風潮の中に広く留まりながら、19世紀後半から20世紀初頭にかけての現象学的精神医学の注目すべき伝統が、明らかに現れた精神的苦痛の生きた経験の説明間の関係を追跡する重要な機会を提供していると我々は提案する。実存哲学や、より広範な社会歴史的時間の説明と並行して。 20世紀初頭のヨーロッパと北アメリカで、時間が科学、芸術、人文科学にわたる激しい議論のテーマとなるにつれ、複数の分野が直感的/主観的時間の説明と数学的/客観的時間の理解の間の緊張を探求した(Fryxell 2019: 5–6) )。現象学的精神医学は、エミール・クレペリン (Broome et al. 2012: 90) によって例示された精神病理への支配的な三人称アプローチを拒否し、一人称、つまり精神状態の混乱に関する主観的な経験に細心の注意を払うことを支持し、この文脈において独特のアプローチを確立した。であること。この学問は、20世紀の最初の30年間に、アンリ・ベルクソンとマルティン・ハイデッガーの時間性に関する新しい哲学に深く影響を受けており、その重要な洞察の1つは、慢性的な精神的苦痛は、生きている時間の感覚の障害として理解できるということでした。しかし、現象学的精神医学は、治療の時間的要求(Fryxell 2019: 23)、つまり臨床的遭遇の相互主観性に縛られた時間、または単に治療にかかる時間には、ほとんど明確な注意を払っていませんでした。しかし、歴史的に現象学的精神医学と並んで登場した精神分析は、複雑で、しばしば果てしなく続くように見える治療の時間性を、特別な自意識とともに反映することを主張した(Freud 1937)。現象学的精神医学と精神分析はどちらも、近代の状況と、工業化された戦争の壊滅的な経験との明確な対話の中で発展しましたが、現象学が精神疾患の経験において後退する正常性の時間的態度を否定的に明確に表現するのに対し、精神分析は精神病理学のリズムと必然性を利用しました。すべての精神生活の構造と、単純に直線的、目的論的、スムーズに流れることのできない時間の精神的生活を照らす方法として、病気になるということ。精神分析は、何もせずに待つ感覚が生きている時間にふさわしいものを壊すということを示唆するのではなく、そのような経験は精神的な生活の避けられない条件の一部であると理解するようになりました。したがって、精神分析は、精神的苦痛の慢性状態を封じ込め、理解し、改善するために、特に慢性的な治療法、つまり時間とケア、そして思い出し、繰り返し、取り組み続けることの提供(Freud 2014)を提供します。この論文は、心の慢性化と忍耐が影響するより広範な心理社会的文脈との間の関連性を強調することによって、「待つのではなく、我慢する」という精神分析の時間的実践の価値について、歴史的に微妙な意味を明らかにすることを目的としている。また、うつ病、一時性、歴史的および心理社会的経験の関係に特に注目することで、英国の国民保健サービスが提供する現代の精神医療における時間の使い方に関する緊急の議論が暫定的に再構築される可能性があることも示唆します。

‘Nothing to be done’ (Beckett 2012: 11). Samuel Beckett’s play Waiting for Godot is not about healthcare, but its first line seems to hover between prognosis and diagnosis, suggesting that some kind of existential ‘doctoring’ is afoot, even as it is clear that no prescriptions are going to be dispensed. For the play’s two central characters, Vladimir and Estragon, ‘nothing to be done’ empties out the urgency of curative political action from Vladimir Lenin’s famous question: ‘What is to be done?’ Every possibility of change on the horizon of the play is derailed by the inertia of the fixing refrain: ‘we’re waiting for Godot’. Waiting is the nothing that famously happened twice (Mercier 1956: 6), and came to be figured, in many early critical receptions of Beckett, as a representation of the existential human condition (Graver and Federman 1979). In the early 1950s, when the play was first performed, perhaps abstractions were more available for critical absorption than the possibility that postwar Europe was still in a present denuded of an inhabitable future (Kenner 1973: 133; Gibson 2010: 108) – an endless time of living on without any real hope of change in the wake of an unspecified disaster. Beckett’s play materializes a waiting that becomes a form of endurance through the promise of what might come to change the present for there is always some orientation towards the future in such practices. But the clear unavailability of Godot decouples the for (Schweizer 2008: 11), the most obvious preposition or relation, from the action of waiting. Neither weak enough to cease and desist nor strong enough to leave, Vladimir and Estragon endure and persist, not, in the end, waiting for Godot but waiting with and sometimes even on one another. Although in this chapter we will pay close attention to existential claims about the place of waiting in human experience, we will suggest that waiting is significantly shaped by the promises and narratives of particular historical moments and lifeworlds, and their distinct ways of understanding time. Indeed, if tarrying in Godot’s waiting room seems to speak to the existential human condition, we would argue that it is because the audiences the play found and continues to find persist in a time when the promises of the future feel increasingly unavailable. Godot’s characters, alongside their audiences, wait with their diagnosis, which is also their prognosis: ‘nothing to be done’. Perhaps one reason the slow modernism of Godot found and made its mark so sharply was its insistence on attending to the disavowed underside of the dominant timescapes of modernity. In 1931, Aldous Huxley was able to state that ‘[s]peed […] provides the one genuinely modern pleasure’ (Huxley 2001: 263), and it has been a critical commonplace to read aesthetic modernism as a reflection of the shock of the new and a pacing, racing present. Planes, trains, and automobiles; ragtime and jazz; epiphanies and revolutions; telegraphs and telephones; production lines and new mass media: humanities scholarship has thoroughly mined how the modernity of the early and mid-twentieth century produced, for better and worse, accelerated lives and shaped technologies capable of both registering and increasing sensations of speed (Duffy 2009). Engaged with a more contemporary moment and less concerned with aesthetic practices, Paul Virilio (2006) has described how a logic of acceleration that has compressed, foreshortened, and fractured time still sits at the heart of modernity and its drives towards destruction; while Jonathan Crary (2013) has critiqued a culture of 24/7 availability fuelled by unsleeping technologies that has turned even the slowing of rest into an act of embodied resistance. But there were always other times folded into the modern, as Elisabeth Kirtsoglou and Bob Simpson’s idea of ‘chronocracy’ suggests (this volume). For example, the managed and mechanized time of the working classes in a newly industrialized Europe was consistently used to service a version of a progressive future that was not shaped in their interests (Thompson 1967). Craig Jeffery has also identified ‘chronic, fruitless waiting’ (Jeffery 2010: 3) as a particular temporal experience of those colonized populations who provided much of the material resources for acceleration of Empire and modernity, noting it as a prominent feature of the experience of subaltern peoples globally since the 1960s. Bendixsen and Eriksen indeed point out that for certain groups waiting can be an expression of power and domination, generating vulnerability and humiliation (2018: 92). And while a ‘new chronic’ temporal imaginary has become more generally palpable in the late liberalism of the contemporary global north (Cazdyn 2012), many of the most acute experiences of ‘chronic, fruitless waiting’ remain ‘zoned’ in specifically gendered, raced, and classed ways. As Lisa Baraitser has argued in Enduring Time (2017), despite an ever-increasing sense of acceleration, because the spooling of time towards a possible future seems to have come unravelled in the contemporary moment, experiences of interruption, suspension, delay, and slowness strongly insist in affective life in highly differential ways. Here, however, we track this sense of time enduring rather than passing back to an earlier moment in the twentieth century, noting the ways in which waiting uncoupled from a future into which one might step came to be understood as a key feature of the affective condition termed ‘melancholia’, or, in its more contemporary configuration, ‘depression’. This is not to claim that either condition is simply a response to modern times or, more strongly still, a social construction; nor is it to seek to medicalize distress that may be the result of other social relations of inequality or injustice (Thomas et al. 2018). Rather, we are interested in exploring how understandings of melancholia in twentieth-century Europe came to be focalized through particular ideas and sensations of stuck, suspended, impeded, or ungraspable time that shaped and continue to mould the contours of the temporal landscapes and psychological imaginaries of (late) modernity. Furthermore, we argue that care in the context of depression, which we understand as imbricated with psychosocial relations and experiences and therefore ‘more than biomedical’ or psychological in constitution (Hinchliffe et al. 2018), may turn out to hinge around the offer and use of extended periods of time and the capacity to stay with those whose experience is that of a temporality that no longer flows. Although the disciplinary perspective here is not anthropological, our concern with examining melancholia and depression through experiences and practices of waiting brings our chapter into contact with an important body of anthropological literature. In his interdisciplinary volume, Ghassen Hage describes waiting as an experience that is always both existential and historically articulated or situational (Hage 2009: 4, 6). Manpreet Janeja and Andreas Bandak similarly suggest that analysing waiting requires a capacity to shuttle between existential and more clearly social or institutional perspectives, as they demonstrate how focussed ethnographic work can illuminate both waiting’s poetics and its politics (Janeja and Bandak 2018: 3). But this chapter uses a more dispersed, eclectic, and textual archive of experience to open up a theoretical account of melancholia/depression as a condition fundamentally entangled with existential, cultural, and socio-historical experiences and theorisations of European (late) modernity. Remaining broadly within the climate of these anthropological approaches to waiting, however, we propose that the remarkable tradition of phenomenological psychiatry from the late nineteenth and early twentieth century provides a significant opportunity to trace the relationship between accounts of lived experience of mental distress that emerged explicitly alongside existential philosophies, and more broadly socio-historical accounts of time. As time became a topic of intense debate across the sciences and arts and humanities in early twentieth century Europe and North America, multiple disciplines explored the tension between accounts of intuitive/subjective time and understandings of mathematical/objective time (Fryxell 2019: 5–6). Phenomenological psychiatry established its distinctive approach in this context by refusing the dominant third-person approach to psychopathology exemplified by Emil Kraepelin (Broome et al. 2012: 90) in favour of paying careful attention to the first person, subjective experience of disruptions of well-being. The discipline was profoundly influenced by the new philosophies of temporality of Henri Bergson and Martin Heidegger in the first three decades of the twentieth century and one of its key insights was that chronic mental distress can be understood as a disturbance of a sense of lived time. However, phenomenological psychiatry paid scant explicit attention to the temporal demands of treatment (Fryxell 2019: 23) – the time bound up in the intersubjectivity of the clinical encounter or simply the time that treatment takes. But psychoanalysis, which emerged alongside phenomenological psychiatry in historical terms, insisted on reflecting, with particular self-consciousness, on the complex, often seemingly interminable temporality of treatment (Freud 1937). Both phenomenological psychiatry and psychoanalysis developed in explicit dialogue with the conditions of modernity and alongside the devastating experiences of industrialized warfare, but while phenomenology negatively articulated a temporal attitude of normalcy that recedes in experiences of mental illness, psychoanalysis used the rhythms of psychopathology and the inevitability of falling ill as a way of illuminating the structures of all mental life and of a psychic life of time that can never be simply linear, teleological, or smoothly flowing. Instead of suggesting that sensations of waiting without a for break apart what is proper to lived time, psychoanalysis comes to understand such experiences to be part of the inevitable conditions of psychic life. Psychoanalysis thus offers up a specifically chronic cure – the offer of time and care, and of remembering, repeating and working through (Freud 2014) – to contain, understand, and ameliorate the chronic condition of mental distress. By highlighting this link between the chronicity of the mind and the broader psychosocial contexts in which endurance plays out, this paper aims to open up a historically nuanced sense of the value of psychoanalytic temporal practices of waiting not for but with. We also suggest that by attending specifically to the relationships between depression, temporality, and historical and psychosocial experience, the urgent debates about uses of time in contemporary mental healthcare delivered by the UK’s National Health Service might tentatively be reframed.

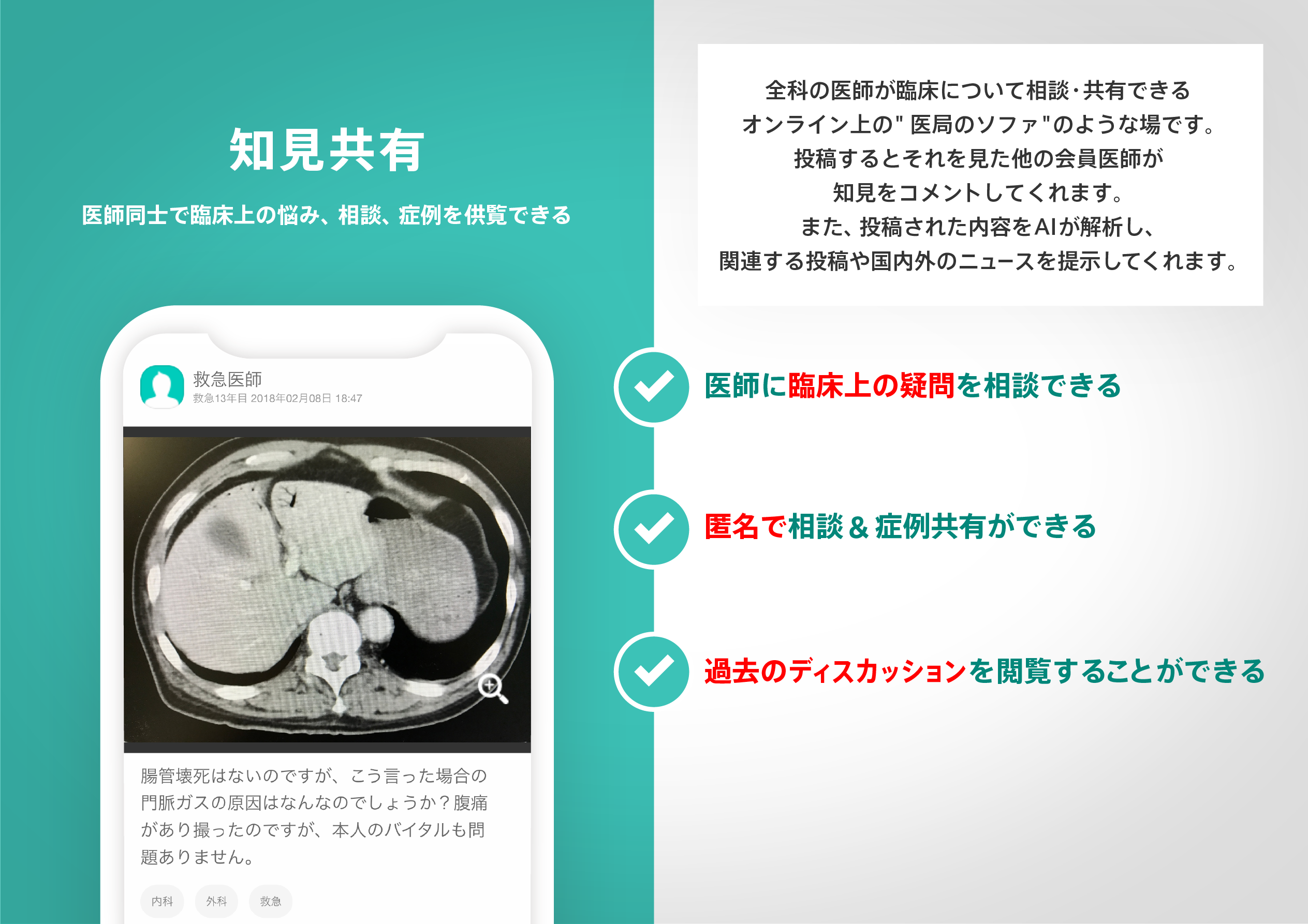

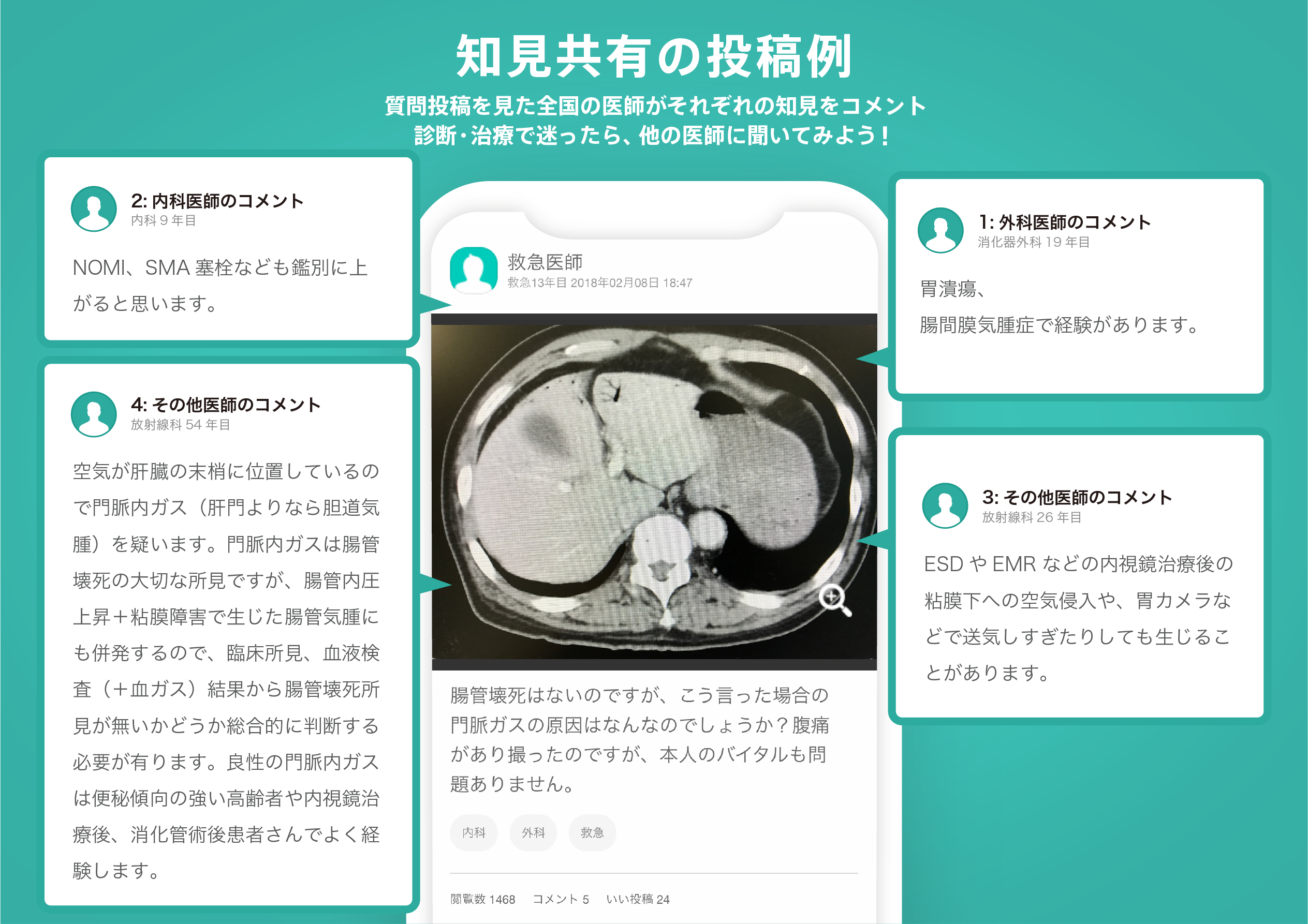

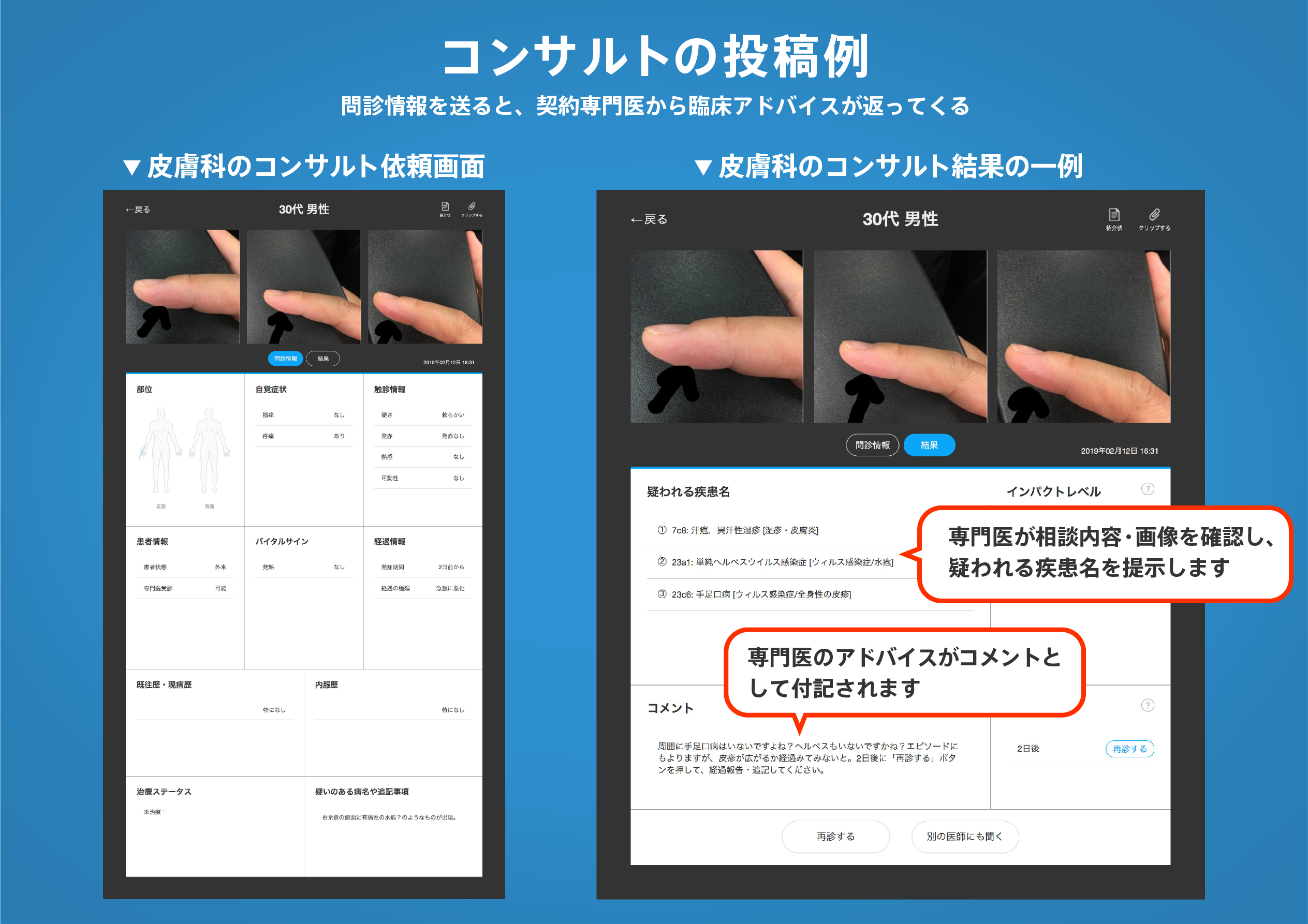

医師のための臨床サポートサービス

ヒポクラ x マイナビのご紹介

無料会員登録していただくと、さらに便利で効率的な検索が可能になります。